The Traveler by vkmack Non-Fiction Writing Contest contest entry |

Dave stood between the depot and the rails, waiting. He had been here many times before, seeing friends and family off to war or to victory, but never alone. No one knew he was going away this evening. Mama had eight other kids still at home, and he would send a telegram back at the first stop.

Dave stood between the depot and the rails, waiting. He had been here many times before, seeing friends and family off to war or to victory, but never alone. No one knew he was going away this evening. Mama had eight other kids still at home, and he would send a telegram back at the first stop.

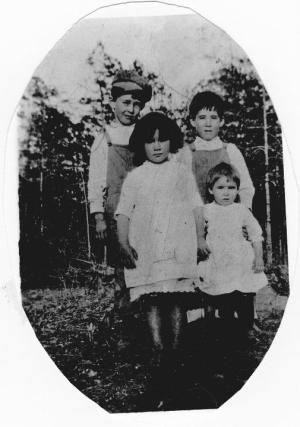

Maybe he was a coward, but someone had to go. It tore his soul away to think of being unable to return on a whim. He had worked the oil rigs and rice fields in the southeastern part of the state, and he had even spent two years as a migrant worker down in the Rio Grande Valley, but the money was gone so quickly. There was always another baby to feed. Mama and Papa did not live together anymore, and she said that their love was dead, but whenever he came around, so did another delivery in diapers. It beat any damn thing Dave had ever seen, but he loved his Mama. He always would. He was the second of her eleven children. Maggie had boys; she had lots of them. Her oldest girl, Clara, did not make it; she had died of "the lockjaw" at twelve. Katie was doing fine, but she had given them a bad scare early on. When she was only two years old, and Papa was supposed to be watching the little ones on "Soap Day," he fell asleep on the porch instead. The baby had toddled right into the fire as soon as Mama pulled the soap pot off. Dave was only four then, but he remembered her screams. They haunted him. Old Dr. Haley came out in his horse and buggy and cut off all the little burned toes on her left foot. "Nothing else he could do," Mama had said that night, through tear-filled eyes. But Maggie and her boys began to hate Papa then. Dave expected he would despise his father all of his life. Still, Clara was the worst loss. Her shiny, black, bobbed hair caught the sun and held it in a way that Dave just could not describe. She had almond-shaped eyes and a pouty, kewpie doll mouth. They were only a year apart in age and even looked alike. He had been so proud of his little sister. After Clara stepped on the nail in the hen house, Mama did everything possible to draw the poison out of her foot, but the girl died anyway. Dave had just turned thirteen then; it was hard to be a man and put her little body in the ground. People meant to be kind. "She was such a beauty," Cousin Nora said. "An angel here, an angel in Heaven," Aunt Ura told him. "She'll never leave you," the Reverend Nations reassured him, with a masculine pat on the shoulder. The boy slept in the milk shed with the cows for two weeks after his sister died. The quiet in the house, the stillness without her, was unbearable. His mother never even cried. Once, when Dave was fifteen, Mama had been lagging behind as the family walked home from the field. Maggie was a tall, raw-boned woman, with a body that bore the burden of two decades of pregnancy and malnutrition. She had paused with exhaustion, placed her hand over her eyes, and scanned the sky. "Look's like a cloud's a-comin'," she remarked. Jim, Dave's younger brother, took off like a shot. "Mama said Clara's comin'," he began to shout at his siblings. "Did y'all hear me? Mama said Clara's comin'. She's comin' back! She wadn't really dead! They made it up! I knew it! Clara's comin' home!" It took Mama all night to calm the boys and Katie down. Dave did what he could. He remembered thinking how simple his family's dream was: the children just wanted to be together. Clara had been gone two years then. So, now he had to leave to keep them together, to make sure that no one else died, to guarantee that it would always be that way. That just struck him as funny--that he had to leave so the kids could stay--and the young man laughed out loud. "If someone sees me, they'll take me to the asylum in Rusk," Dave thought to himself. He looked like a scarecrow, and that was not helping. All his possessions were folded into an old brown leather satchel borrowed from Uncle Gene. The inventory totaled one decent work shirt, a pair of khaki pants, a good pair of boxer shorts, one A-type undershirt, a razor and blades, shaving soap and brush, toothbrush and tooth powder, and a bar of homemade lye soap. He wore his only other suit of clothes and underwear, and they now smelled slightly perfumed--a mixture of fresh bath water and sweat from the long walk into town. The squeal of sparking steel ripped through the quiet of the evening. The train was just down the line; it would be here in no more than a minute. He was surprised by the clarity of his thoughts. No point in worrying now. He had to go. Mama wore his good shoes to church on Sunday, so she would not be barefoot. They had not seen Papa in months. The cotton market had gone straight to hell. Even with his oldest brother, Olaf, and their little sister, Katie, married now, Mama still all those children at home, and she would never make it. He had to do something. The Civilian Conservation Corps recruiter had been real nice. Dave had been thinking hard on going into the CCC's for a long time now. Several of the other farm boys had headed out, and they liked it. Their letters home talked about food--more chicken and mashed potatoes than anyone in Goodwin could imagine--and faraway places like New Mexico and Mississippi. Dave read the newspapers when people gave them to him, and he wanted to see a few places before death caught up to life. He spoke no foreign languages, so he would never belong in Paris or Rome, and Yankees were unfriendly folks who called him a stupid Hillbilly. But why not try another town down South? He listened to the songs on the radio and heard the hobos talk about riding the rails. "All around the water tank, waitin' on the train," Jimmie Rodgers yodeled. Well, now he was waiting for it, too. Twenty minutes later, when the conductor punched the government-issue ticket, he watched his little town roll away into the dusk. Rocking and swaying with the locomotive, he settled in for the ride to Tenaha. The depot there had a telegraph office, and he would send the wire back to Goodwin for Mama and the kids. Gone to CCC. Sending money. Dave Finally on board a car actually chugging away into the future, he felt important for the first time in his life. When the sun came up, no one would find him hunched in the cow shed, urging Bossy or Bess to "Give, girl, come on now," though the poor old bovines were both worn down and close to dry long ago. Mama would rise with the rooster, build a fire in the stove, and put the kettle on. She would shove the fresh biscuits into the oven and drink her chicory while they baked. This was her only time to sit alone; no one ever disturbed her. When breakfast was done, she would take the cast iron skillet from the heat and set it on the stovetop, so the boys could each take a biscuit, pull it open, and pour it full of sorghum molasses on their way to join her in the field. But he would never appear, the tallest of her children still at home, long-boned and lanky, raven-black shock of hair hanging in his sad, gray eyes. They set so deep and dejected in the young man's tired face that people talked about how old he looked. Though only twenty, Dave felt every second of this life. And he wore time the way other people wore heavy winter coats; memories weighed him down, but they also kept him warm. Now, he was gone. He stared out the window into the disappearing sunset. The sky was ablaze with maroon and coral, as the treetops grew black, seeming to extinguish the day. Dave loved this country almost as much as he loved Mama and the kids. Sometimes, he worried that he loved the land more. It turned for him. Things grew from it. While the family never got much for sharecropping, they always got something. Farming on shares was better than following crops down in the Rio Grande Valley, where it was hot and dry. In the migrant camps, foremen paid pickers only a penny a bushel. The little ones could not do enough work to make any money, and Dave could no longer justify uprooting them for that sort of business. But he did not care to go down there alone anymore either. At least now, on Uncle Gene's place, they did not have to pack up and move every time the season changed. And while they might be poor, none of them were starving. It seemed that babies just kept coming. Mama was in her forties, but Dave had a new sister. This little girl had hair the same blue-black as his, and she was walking and talking. Each day, they sat her on a blanket in the shade, while the boys and their mother chopped cotton. They had painted some old thread spools to string together for her, and she had her own baby made of rags. She was so much like Little Clara. He did not want this child to grow up with only worry and change and worry about change. Something had to happen. So he made it happen. Maybe Mama would forgive him for running. Maybe she would understand why. Someone behind him was laughing. Dave was feeling better than he had in a long time. He would meet new people now, folks from all over. Other boys said they met guys from as far away as El Paso, and men from other states were coming to Texas for this work, too. They built dams, stocked ponds, created drainage systems, fought forest fires, built roadside rest stops, and even planted trees. He could plant anything; he knew that already. Maybe that would be how they started him out. One of the Quinn cousins had learned to dig irrigation ditches and water wells. He sure would like to learn how to do that. That would be a real trade for a man to have. The best thing about this was the pay. The government offered him $30.00. Dave had never seen that much money at one time in his life. Uncle Gene always dealt with the cotton merchants in town and then gave him receipts and a little money. But he gave it to Mama the same way it was handed to him--in a sealed envelope. They never earned enough to buy shoes for all the kids, so that meant it was not sufficient anymore. The man at the CCC office said that the government would send Mama a check every month. The CCC people wanted him to keep $5.00 for himself, but Dave did not like the idea. "No sir," he told the agent in San Augustine, "I ain't got no use fer that kinda money." "Son, you'll be far away from home. You'll want to have some fun, and you will need a little cash." The man had looked at him kindly, but Dave could tell when someone thought he was not very intelligent. "No, I ain't goin' fer fun. That's not why I'm leavin'," he had said, with determination. "I'll sign whatever you got there, so long as it gives it all to my mama. But I don't want no money fer me." "Well," prospects were waiting in line, and the agent did not want to spend time arguing with this stubborn young man, "let me ask you a question. Do you dip or chew?' "No sir, I don't do neither one." "Well, that's unusual. Do you smoke, then?" Dave had not thought of that. He and his brother, Olaf, had started rolling their own cigarettes when they were just eight and nine years old. "Yes sir, I do roll my own," he had admitted, sheepishly. For the first time, he felt a little ashamed of smoking. "Tell you what, Son. I'll put down here that we are sending $29.00 a month to Maggie Holloway, and then you can keep a dollar for cigarettes and whatever else you like. How does that sound?" "Uh, well, I figure I ought to quit smokin'. I been at it fer twelve years now, and them people are proud of their Bugle Boy these days." "Let me tell you something, Mr. Holloway," Dave could see that the man, though more than slightly frustrated, was still trying to be polite. "If I send you off to El Paso or Albuquerque or Arizona without a penny to your name, and you need anything at all, but have no money, I might lose my job. So, I'm going to assign one dollar a month to you and the rest to your mother. That will protect us both. Do we understand what I mean?" "Yes sir, I do. I reckin that would be fine," Dave conceded. He was beginning to feel guilty about being so stubborn. This man was offering him a great opportunity. So, they had signed the papers, he had picked up his travelling ticket, and now here he was on the train to his future. It rocked and rolled on into the night. Tenaha was coming up soon. He would send the telegram, and one of the boys would read it to Mama, who had never learned to read. She would understand when the first check came, and she could buy a real pair of shoes for herself. Now, when she walked through the woods to church, no one would have to worry about how hard her love of the Lord was on those poor, bare feet. When winter came, the children could have new coats--but he would be gone. It was worth it. He shut his eyes and pictured home. Supper time had arrived. He could smell the cornbread and pinto beans. That was what they had almost every night. Who would rock the baby to sleep? Maybe Jim or Willie Rudolph would do it. The younger boys could be helpful when they wanted to be, but they would fuss; long days in the field made them tired and cranky. Well, they would learn to get along, and things would be fine. He smiled. "Goodnight, Mama. Goodnight, Boys. Goodnight, Katie. Goodnight, Rosie," he mumbled under his breath. Then, he did what he did each night. He closed his eyes again and thought of someone he had lost so long ago. "Goodnight, Clara. See you someday," he whispered. "Tenaha," shouted the conductor. "Tennnnn-ahawwwwww, comin' up!"

|

| ©

Copyright 2024.

vkmack

All rights reserved. vkmack has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work. |