![]()

By CM Kelly

"Can You See The Real Me?" is my second book, it is a collection of ten stories broken into two groupings. The stories have been chronologically arranged, the initial grouping is based on a few of my coal mining experiences, which can only be described as "unique". The second grouping relates to the politics that I found myself immersed in, or better described as "tangled in" as I plodded through my career.

As I wrote these stories, I weaved in quite a few details about underground coal mining and a fair amount of background material that one rarely finds in books these days. I hope these educational sections don't bore you. I do hope that the scary and funny parts make for a nice balance.

Every story is rooted in an actual experience. The names and exact sequences have faded over the years, the stories may be a little embellished, and repetitive, but they are all based on true events.

As you read these stories, try and place yourself in my shoes (or hard-toed boots). I am sure it will make reading them a tad more interesting.

I hope you enjoy them.

| Author Notes |

Warning - This is a Novella. I wrote this with the mindset of explaining and providing details not typically seen in short stories. In a way, I hope it is educational as I tried to describe the details of underground coal mining and power plant construction/operations. I lack professional training or writing experience. I hated my HS/College English and literature classes. My passion has always been engineering, with a focus on numbers, formulas, equations, and algorithms. Thus, the two Engineering Degrees. Somehow I obtained some management-people skills that helped me climb the corporate ladder. All of my stories are based on actual events, of course with some embellishment.

|

![]()

By CM Kelly

"Blackie, we can't get Junior killed on his first day."

It's hard for me to imagine being more anxious about starting a job than that spring day I sat at the end of a wooden bench just outside the bathhouse of the Montour #10 underground coal mine. I had just finished my junior year at Penn State as a Mining Engineer major and my gut had been telling me for over three years that I had to get some real underground experience before I graduated. For students in the Mining Engineering program, there was a requirement to undertake a six-month internship within the mining industry to earn their degree. As such, I fulfilled that obligation by doing a six-month stint with Consolidation Coal in their Engineering Department the prior year. I could have returned to the Engineering position but I knew that having some underground experience would greatly enhance my resume. More important to me was the simple fact that since the moment I decided to become a Mining Engineer, I had this calling within me, an inner desire, to get firsthand experience of working underground. I was that kind of a guy, I had to get my hands dirty, I had to apply what I was learning in the classroom in the field.

Yes, I had been underground once before as part of a surveying course. It was basically a one-day tour of an underground limestone mine just outside of Penn State. By coal mining standards, it was a pretty tame experience, with no methane, no coal dust, 20-foot tall ceilings (in the mining industry we call it a roof), and 40-foot wide tunnels (that we call entryways or entries). In general, limestone or hard rock mining, although dangerous and difficult work, was nothing like underground coal mining. Whether it be the physical nature of the material or the fact of working in a methane-laden atmosphere, traversing flooded entries, or working in 3-5 foot tall seams, underground coal mining was unique. Layer on top of all that, the tensions and conflicts between the miners and the coal operators, it put underground coal mining in a category all by itself.

I sat there on the bench in my worn jeans and heavy work shirt, standing out amongst the other general laborers, not so much with my youthful look, but rather with the bright red hard hat I was wearing. The red hard hat, aka red-cap, signified that I had less than 90 days of underground experience. It was a safety feature that let the other miners know there was a "newbie" in the area. It also signified that a red-cap worker could not operate any machinery. So I sat there hiding my nerves on the dirty, worn, and tired bench with three other general laborers waiting for the Shift Foreman to assign us our work.

Montour #10 was one of forty or so mines that Consolidation Coal owned and operated. Located about 20 miles south of Pittsburgh, near the town of Library, it mined the Pittsburgh Coal Seam. Based on the rusted-through steel members of the rail facilities and the condition of the bathhouse, it looked like it was started or opened around WWII, making it at least 10 years older than me. The mine produced high-grade metallurgical coal that fed the coke mills up and down the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers.

The Shift Foreman, a crusty old man who looked like he hadn't had a bath nor his clothes washed in about a month, stepped over to me and said sternly, "Son we expect a day's worth of work for a day's pay, you'll be working with Paul today." At this point in my life, I was 20 years old, 6 feet tall and 160 pounds, lean and mean (as Bob Seager would sing, "like a rock") and no stranger to hard work, but still, that phrase is seared into my brain.

I was anxious and nervous, but I was also well-versed in the use of a shovel, pick, and sledgehammer. I had the thick calluses on my hands to prove it. I had no inkling of what kind of work would be required of me for that shift or the remainder of my six-month stint.

My head was flooded with questions: could I handle the darkness, what would it be like working with essentially a flashlight on my head, what would the air be like, what would it smell like, and how would the union miners accept this college kid? Hundreds of other thoughts ran through my head, the least not being, "What if I couldn't hack it?" I had invested three years in school pursuing my Mining Engineer degree, would it all go to waste? I had to get underground to bring an end to these questions.

A short-scraggly old man, looking more like a railroad hobo, walked up to me and said, "You're with me, come along." He had a noticeable limp, hadn't shaved in a week, and was carrying a thermos bottle. A second glance at him made me realize that he looked exactly like Festus of Gun Smoke fame. Like the Shift Foreman, he too, hadn't seen a bar of soap in over a month. I guessed he was in his 50s, but with a dirty unshaved face, he could have been anywhere between 40 and 60.

By now the bulk of the mine's workforce of over 100 workers had proceeded towards the underground mine's entry. They climbed into their mantrips and headed down the slope. Montour #10 was a slope mine, a description used to describe an underground mine where the coal seam intersected the surface, thus it did not have a shaft with an elevator. I grabbed my miner's lunch pail with its shiny bright new aluminum exterior. It made a sharp contrast against the other workers' lunch pails that were dented, tarnished, dirty, and covered with union stickers. As I started to follow "Festus", two other miners joined up with us. One was a middle-aged man, of regular build named Paul. The other was a young man, Ben, maybe 8 to 10 years older than me and built like me, a little on the tall slender side. They didn't say hello or anything, but I quickly gathered that the four of us were some kind of a crew and would be working together for that shift.

We walked across the supply yard, carefully ducking under the live trolley wires, and into the mine along the main entry. The main entry had rail tracks just slightly off the centerline to the left. It was a typical rail system with medium-duty iron rails and wooden railroad ties, the kind you see hauling freight and passengers around America. The rail system was the backbone of this underground mine, it transported the men and supplies and more importantly, it was how they brought out the coal. The locomotives and mantrips that used these rails were a low profile type so as to fit in the 5 to 6-foot tall coal seam. They were powered by the 300-volt DC power trolley cable, 1.5 inches of bare, uninsulated solid copper which was hung from the mine's roof via ceramic insulators. We walked on the wide side of the rail, more commonly called track, specifically on the right side; the pathway was about 4-5 feet wide, just enough for two men to walk side by side.

The energized trolley wire was on the other side, the wide walkway and the 4-foot wide tracks providing some degree of safety. The total width of the entryway was about 14, maybe 15 feet. The coal seam was about six feet tall. With the protruding roof bolts and cross beams holding up the roof, it created an effective working height of about 5 feet. Just enough to make me have to slightly bend my back or neck to avoid bumping my head. But that was ok since I had to keep the headlight on my hard hat focused down by my toes. After a minute or two I began to realize that if a locomotive or mantrip came down the rail it would be a tight fit. At that point, safety, specifically my safety, trumped all the questions floating in my head.

The pace was quick, and after about 500 feet into the mine, the morning sunlight streaming down the track from the opening behind us had diminished enough that we all turned on our headlamps. For this novice miner, walking underground, along the uneven terrain, in a pitch-black environment, using the headlamp on my hard hat as a flashlight was a general thrill. Yes, I am one of those types of guys who would think a situation like this was fun. Now my biggest fear was that of falling flat on my face and embarrassing myself.

We walked for another 10 minutes and I began to feel a little more comfortable with the underground surroundings. From my mining courses, I recognized the cross cuts intersecting the track entry and assumed the pattern of these blocks of coal were optimized for roof support. After a few more minutes it was obvious that my slower, more tourist/cautious gait was not going to keep up with the others, now I began to worry about getting left behind. Maybe that was their intent, some form of a first day-on-the-job joke for the newbie. Just about when I was about to admit defeat and cry out, "Hey guys hold up", I heard a rumble in the distance.

As if my senses weren't already on overload, with the high voltage line on the left, the dark damp environment, uneven footing and just generally being my 1st time in an underground coal mine, now I was hearing a growing rumble coming from within the mine. Within a second I realized it was not a roof fall or explosion, but rather something was coming at us on the rails. The track bent off to the right in a downward fashion, it wasn't hard to see the flicker of the locomotive's light hitting the far left corner of the roof. The light and the noise were growing, I surmised the situation and thought of all the TV or movie scenes where some unsuspecting teens found themselves in a railroad tunnel or along a rail bridge in the same predicament. But I thought the wide walkway would be enough and I could just lay tight against the side of the coal pillar and be safe. That's when I saw a hard hat headlight walking back towards me in a hurried fashion. It was Paul, in a direct one he said, "We got a trip of loads coming out, we need to duck into this manhole".

With that, we took a few steps backward and I realized that in the 90-foot-long pillar of coal, there was a 5-foot wide, maybe 3-foot deep cut in the coal, just enough for the two of us to squeeze into. By the time we positioned ourselves into the cut-out, the 30-ton locomotive with its trip of loaded railcars, full of freshly cut coal, was upon us. About twenty 10-ton coal cars whooshed by, the edge of the loaded cars seemed to be about a foot from my nose. I now realized that the rail cars were much wider than the tracks. If I had laid against the coal pillar I may not have been squeezed by a rail car but I could have easily been hit by some of the dangling wooden posts hanging out from the sides of the coal cars. It was a little scary but I never felt anxiety, worried, or panic. Maybe, just maybe, I liked this excitement. No doubt this little event helped reaffirm in my mind that working underground was in my blood. The trip of loaded cars went by and Paul stepped out and started walking back into the mine; no words, just actions, no BS, no hype, no snide comment, just a "get back to work" attitude. Another example of why I wanted to work underground.

We caught up to "Festus" and Ben who were sitting back in a crosscut, maybe 20 feet in from the rail track, much-much further back from the rail line than what Paul and I were just a few moments ago. They got up and started to walk with us. I could hear Paul say to "Festus", "Blackie, we can't get Junior killed on his first day." That's when I learned that Festus had a name, "Blackie", and that my nickname would be "Junior". We walked for at least another 30 minutes before we stopped.

We were deep in the coal mine; we had traversed way too many turns and twists for me to remember how far we had come. Now I had a new fear, I had to make sure I never lost sight of the other three because there was no way I would ever be able to find my way back out to the surface. We stopped at a cross-cut, there were a few crude benches on the right side up against the coal rib. Clearly, this was a marshaling place for this crew. The others took off their heavy, mainly corduroy coats and hung them from a roof bolt with their lunch pail. I placed my jacket on a piece of 4x4 wood cribbing and put my lunch pail beneath it. Blackie came over to me, briskly grabbed the pail, and said "You need to keep that off the ground, the rats in this mine are so big they can eat right through the metal sides". This would be the first of many, many jokes Blackie would say to me over the coming months, sometimes testing my nerve and always playing off my inexperience. Eventually, I would learn that he was the funny guy, the comic, and that Paul was the straight man in this duo.

I surveyed the immediate area, not an easy task with the small headlight on my red cap. There were stacks of railroad ties, a pile of 30-foot-long track, and numerous 5-gallon buckets filled with rail spikes, bolts, and nuts. Now I knew my destiny for this day, I was on the track crew.

For the rest of the shift, we worked on laying track. It was just like you would see in the movies, we carried the railroad ties on our shoulders for about 100 or so feet and dropped them on the ballast/recycled slag. After we laid about a dozen of them down, we would then haul in a 30-foot section of rail. We would take turns using a sledgehammer to drive in the rail spikes. I was no stranger to a sledgehammer, but it would be weeks before I could drive a 6-inch spike with just one blow. We probably laid about 150 feet before Paul said, "It's time for lunch." As hard as the work was I was not tired at all. This gave me some inner comfort, that physically I could stand my ground with them.

We went back to where we laid our coats and lunch pails. I was warm from the workout, the other put on their jackets, clearly they knew something I didn't. They sat down on a bucket or piece of cribbing, about 10 feet apart from each other, close enough to talk, but far away from each other to stake out their own domain. I could tell Paul had a pastrami sandwich, while Ben had some kind of stew, not from seeing them, it was too dark for that, but from the smell. No doubt when you are underground your senses are all on full alert, listening, seeing, feeling, and smelling for anything different. It was at this point that I realized that Blackie didn't bring a lunch pail. He just had his thermos with coffee in it, or at least that's what I assumed was in it. Although the outside temperature was in the 70s, the 50-degree air in the mine combined with my sweat, created a chill within me, so I put on my jacket. There wasn't much talk among the crew. After they finished their lunch, they turned off their cap lights and took a 10-minute snooze. Of course, I was too excited to take a nap. I just sat there and observed the surroundings.

After about 15 minutes, Paul stood up and said, "Time to get back to work." We spent the rest of the afternoon laying about 90 more feet of track plus shoveling slag around the railroad ties. Hard work, but not as intense as the morning. After a few weeks of working underground, I realized that I worked just as hard hand digging out the basement of our 1800s farmhouse during my high school years.

At the end of the shift, the walk out of the mine did not have the drama of a trip of loads coming by, but it gave me some time to reflect on what my first shift underground was like, what I learned and what I accomplished. As we made the final turn on the track entry, I looked up from watching my toes and saw that small glimmer of sunlight in the distance. It signaled more than the end of the shift; it acknowledged that I had survived my first shift underground. It's a memory I have never forgotten. In today's vernacular, one would say, it was the moment I affirmed my calling or found my passion.

After we reached the surface, we punched out our time cards and I headed into the bathhouse. I skipped the shower, washed my face and neck, changed my shoes, and headed to the parking lot with the 100+ other miners.

Before I knew it I was back at the summer apartment I shared with two other Penn Staters, tired but not sore. I had a healthy appetite that evening and went to bed early, with little time for reflection, but I knew it was a "good day". The last thing I remember was double checking the alarm clock for the next day's 4:30 am wakeup.

*****

There would be many other events, experiences, stories, and memories from that six-month stint. I not only learned how to lay track, but I was also educated on what fish plates and frogs were, how to use a spad gun, install brattice/vent curtains, build cribs, install breaker posts, build stoppings, how to use a safety lamp, and most importantly: how to sound a roof and what lock-out-tag-out means.

I carried my share of cinder blocks, timbers, railroad ties, bags of rock dust, armor and wooden ties, roof bolts, and glue cartridges. I shoveled tons of coal and slag. How could I ever forget that Blackie taught me how to play baseball with a pocket knife, which we played almost every lunch. But I never learned how to chew tobacco or use snuff, boy, could Blackie chew and spit that "to-bacca".

I did face a few life-threatening events, including being electrocuted and almost crushed to death. Stories for another day. It was hard work by any standard, but I truly enjoyed it. There is a sense of pride, one of accomplishment in "putting in a day's work for a day's pay".

Looking back, it turned out that Blackie and Paul were really my first mentors, and honestly, probably the best mentors that I had over a 40+ year career.

At the dinner hole, after a few weeks, the track crew eventually did strike up some conversations. Blackie was a second-generation Italian and spoke Italian very well. He had a wife that he adored, no children, and loved his red wine with dinner. Paul was an ex-Middle School English Teacher, but found the work, and money, provided by the mine more rewarding. Both were the silent type, strong in character but light on words. Ben was a high school dropout, quite the chatterer, in this group, and he had a great sense of humor. Over the summer, we shared many jokes and stories, a friendship developed bonded by sweat and coal dust.

++++

I worked as a card-carrying member of the United Mine Workers of America on the track crew for most of the summer. Occasionally I got "drafted" by another Foreman to put up posts or build cribbing in the old returns, move power cables, shovel spilled coal, install stoppings, or help load/unload supplies. By the end of my stint at Montour #10, everyone at the mine knew who Junior was.

On my last day, Blackie tried to slip me $100, but I absolutely refused it. He and Paul gave me something far exceeding anything that could be captured with money. But I could tell by his voice that it was important to him that I take it, in a way it symbolized that he and Paul would always be helping, maybe guiding, me as I went through my career.

Back at school, it took another three months to "sweat out" the black dust that was embedded in my pores. No doubt, my time at Montour #10 laid the foundation for my mining career. It established my work ethic and my deep commitment to safety; I learned a lot and I grew up a lot during that stint underground.

Yes, I probably reflect back on that time a little too often, but I don't consider that a bad thing.

| Author Notes |

This is one of ten Novellas. I wrote these Novellas with the mindset of explaining and providing details not typically seen in short stories. In a way, I hope it is educational as I tried to describe the details of underground coal mining and power plant construction/operations. I lack professional training or writing experience. I hated my HS/College English and literature classes. My passion has always been engineering, with a focus on numbers, formulas, equations, and algorithms. Thus, the two Engineering Degrees. Somehow I obtained some management-people skills that helped me climb the corporate ladder. All of my stories are based on actual events, of course with dash of embellishment.

|

![]()

By CM Kelly

.png)

| Author Notes | These short stories are all from an introverted, wide-eyed, green hick, the 4th of 9, raised on a dirt road, one who never in a million years thought that he would wind up in the places or the situations described in the stories. With two engineering degrees, I lack any formal training when it comes to writing, but I find writing to be "fun" and "enjoyable" and a great tool to keep my memory sharp. |

![]()

By CM Kelly

| Author Notes |

I lack professional writing experience. My passion has always been engineering, with a focus on numbers, formulas, equations, and algorithms. Expect straightforward prose; you won't find complex vocabulary or four-syllable words. The 4th of 9, raised in an abandoned farmhouse on a dirt road, there's a degree of wonderment, aka Forrest Gump, weaved throughout these stories, which reflects my, hick from the Sticks, personality. All of my stories are based on an actual events. You will like these stories if you enjoy Mike Rowe's books (aka Dirty Jobs).

|

![]()

By CM Kelly

| Author Notes |

I lack professional writing experience. I hated English and literature classes. My passion has always been engineering, with a focus on numbers, formulas, equations, and algorithms. Thus the two Engineering Degrees. Expect straightforward prose; you won't find complex vocabulary or many four-syllable words. As the 4th of 9, raised in an abandoned farmhouse on a dirt road, there's a degree of wonderment, aka Forrest Gump, weaved throughout these stories, which reflects my, "Hick from the Sticks", personality. All of my stories are based on actual events, of course with some embellishment.

|

![]()

By CM Kelly

The drive to Dilworth Mine was always my favorite. It only took about two minutes after leaving the office to get on Interstate 79 South. A few minutes later, after skirting around Little Washington, it was a rather straight shot down to Waynesburg and the exit to take the back roads to Dilworth. This exit provided me with one of my favorite quick food stops, Wendy's. With its dollar menu, it was a bargain stop for lunch or dinner. It only took one visit to get me hooked on its Junior Bacon Cheeseburger and Biggie Cokes, each just a dollar!

Waynesburg turned out to be a pivotal location in my work-related travels. This exit was an equidistant 30 minutes from the regional office, Dilworth Mine, the Robena Prep plant, and the Bailey Mine. Waynesburg had a lot of history and thus a lot of character. To reach Bailey Mine I had to drive through the town. It had a nice two-lane main street that went through some neighborhoods built in the 1800s. Some of the homes were mansions, but like almost every coal mine or steel town of that period, they were well past their prime.

Occasionally you would see one home immaculately maintained while most of the surrounding homes were in decay. Made me wonder about the person or family that lived in the immaculately maintained home, was it pride or stubbornness? Were they just fighting the inevitable decline of small towns, hoping, and praying for good times to return, or just keeping the family homestead in good standing since they may have lived there their whole life.

Just before the Waynesburg exit, about 5 miles, there was another exit that dumped off into a local road. There was nothing and I mean nothing at this exit. However, this exit did lead me to my very first work assignments when I worked in the regional office. Both involved the closed Robena Mine.

Consol had bought the Robena Mines #1, #2, #3, the associated Robena Prep Plant, and the Dilworth mine a few years earlier from US Steel.

The Robena Mines & the Prep Plant were located along the Monongahela River (the "Mon") about 20 miles from Pittsburgh. This mine was opened around WWII, and its coal reserves were extensive, with a peak employment of around 1,200. It supplied metallurgical coal to the Clairton Coke works that fed the steel mills around Pittsburgh. It was the economic backbone for the surrounding communities like Mather, Jefferson, and Carmichaels.

The Robena underground mines were all shut down when the underground travel distance between the working faces and the prep plant became too great. Consuming an hour to transport workers and supplies from a portal to the working face, reduced an 8-hour shift to a 6-hour shift. Two hours of no productivity really hurt the bottom line. Additionally, the distance to haul out the coal also impacted the mine's economics. The Robena mines utilized an electric rail haulage system, but with over a 10-mile haul, the effort (as in $) and risk (as in a roof falls and related maintenance) of keeping the 10-mile-long rail haul route open put an additional cost burden on the mine.

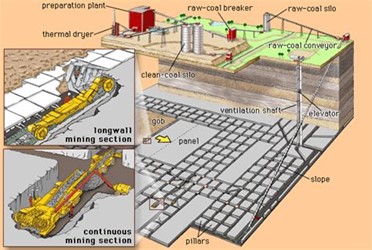

The Dilworth mine, located a few miles north, near Rices Landing was opened up in the early 1970s. Although the initial 10 years of the mine's life utilized the room and pillar mining method, it was built with a modern conveyor belt haulage system. Its coal rose to the surface near Rices Landing on the Mon river, via a slope entry. The coal was then loaded onto barges and shipped a few miles downriver to the much older Robena Prep Plant. Dilworth had a fair amount of coal reserves remaining; thus a longwall mining unit was added in the early 80's.

A couple of notes about longwall mining;

First, it is a much more productive means of removing coal. With its dual cutting heads slicing off 30-36 inch deep swaths of coal along a 600-foot-wide face, the tons per shift, aka production rate, dwarfed that of any Continuous Miner (CM) units.

Secondly there is nothing in the world (above or below ground) like it. It is the purest form of converting electrical energy into mechanical energy that I have ever experienced. With other devices that convert energy like pumps, motors, fans, gas turbines, jet engines, and so on, nothing, and I mean nothing, compares to standing 3-4 feet away from the brute force being generated by those twin 400 hp cutting motors as they dig into the coal face. It's Man versus Mother Nature at its best.

Note; Longwall units have increased in size significantly since the '80s, the face widths now exceed 1000 ft and the machines can cut up to 42 inches deep. The cutting head's horsepower now exceeds 800hp. Technology marches on.

++++

I had just taken the position as Project Engineer at Consol's Eastern Region. My three initial tasks at Robena involved backfilling an old air shaft site, demolishing an old portal and installing a 1 mile natural gas line. They were rather small projects but provided me with some field experience that I needed.

Topping off the old Robena # 3-Kirby Air Shaft was needed because the initial backfilling that had been done two years earlier had settled about 20 feet. Something "settling 20 feet" may sound like a lot but if it's a 600-foot-deep air shaft that is less than 5%. It was an easy task where I lined up a local contractor with a backhoe to excavate the needed material from the nearby hillside and top off the shaft.

It only took half a day for the contractor to fill the void and leave a 5 ft mound on top. I had the contractor also pile up mounds of dirt at the shaft entrance just off the gravel road, hoping that would keep any teenage partiers from getting close to it.

Several months after the work had been completed I stopped by the site to see if the 5-foot mound had settled. Fortunately, it did not. I figured this would be my last stop at this location forever, so instead of heading back to the Interstate I went up further into the holler. Not having any idea of what I would find. I figured I was not trespassing it logically seemed to be part of the old mine property. As I trekked further I convinced myself that maybe there was a mine borehole or power line that needed my attention. This gave me a reason to proceed further. After a few hundred yards the road took a sharp turn upwards, the spinning back tires required that I put the company tuck into 4-wheel drive. I climbed the gravel road for about another 2 miles to a point where it hit the crest of a ridge. The gravel road ended at a farmer's gate. What lay before me was an absolutely stunning cow pasture of about 100 acres and an unimpeded view of Western Pennsylvania all the way to the West Virginia border.

The view was phenomenal, I made a point to myself to come back sometime in the fall to see it coated in its fall colors. Before I climbed back into the pickup truck I checked the immediate area around the back and sides of the truck making sure I had enough room to turn the pickup truck around. At that point, I noticed that the ridge line was delineated by an old stone fence. For the most part, these fences were created in the late 1700s through the mid-1900s. One could only imagine the work it took to haul these stones from the fields below and build this wall on the top of the ridge line.

I walked the stone fence line a little, recollecting the same stone fences that surrounded the fields where I grew up in Eastern Pennsylvania. It only took another second to remember that these stone walls typically harbored snakes, lots of snakes! As I briskly walked back to the truck I noticed a tall slender stone that stood out. A closer look revealed it was a hand-cut obelisk, made of sandstone. It was some kind of a marker. Hoping it wasn't a grave marker, I moved some branches and a few stones and realized it was a surveyor's marker. It was old and worn but I could tell from the carved letter and initials it had on it: N39-47-26, 80-05-25W, 1750, GW. For a moment I thought maybe George Washington surveyed this area and stood on this very spot taking in the same vista view.

Pretty cool I thought, it's been well over 30 years since I found that marker, and going back to that location, on a crisp fall day, will have to be on my retirement bucket list.

++++

The second task was the demolition of the abandoned Bowlby Portal at the Robena # 3 Mine. The portal was built in the 1950s and shut down in the early 80's. It had served a very useful 30 years. The elevator and associated equipment had been removed and the shaft filled in a few years earlier.

Consol had left the portal building intact, hoping that someone would buy it and turn it into a small machine shop or some other light industrial facility. Not an unreasonable position considering it had existing water and sewage facilities plus a hefty power line and substation. However, a potential buyer looked at the property and realized it had significant asbestos issues and backed out of a deal. The word was out, no one would look at the building.

With the asbestos issue, Consol decided to demolish the building. That's where I came in. So I pulled together a bidding document, adding in the qualification that the contractor must be approved to remove asbestos. The oversight on this project was rather minimal.

The two strongest impressions from this project that remain with me were: walking through the portal/bathhouse on my first trip to the site. It looked like time had frozen, I knew the mine had shut down at least three years earlier, but the place looked like it was evacuated in an emergency.

Miner clothes were still hanging in the bathhouse baskets, the offices were locked, and peering into the offices revealed that they looked like they were ready for someone to go back to work the next day. There were even some old vending machines with old chips and candy in them. This place was so isolated that not even curious teenagers had found it. One could only assume that the shutdown occurred on a specific day with mine management at the gate and security guards standing by their side. The workers were probably given a few minutes to collect their clothes and handed their last paycheck. That was it. Decades of mining, the economic backbone of the area for generations, a workplace where men gave their sweat, muscles, and lives all gone in a day.

^ FOOTNOTE: The Robena # 3 mine had a major disaster at the nearby Frosty Run Portal on December 6, 1962, 37 men perished that day. A memorial can be found along Interstate 79 just south of Waynesburg.

The second memory I have from this project was the removal of asbestos in the old bathhouse. This was the mid-80s when the asbestos fear was at its peak. Before awarding the demolition contract I had to determine what areas of the old building had asbestos.

In this case, the ceiling and floor tiles had some non-friable asbestos, which required it to be bagged up and disposed of at an approved site. But the old oil-fired boiler and hot water system for this portal of about 300 workers was encased in friable asbestos. Removal of this material involved the full enchilada. Setting up a controlled area with plastic tarps, wetting it down, and slowly and painstakingly removing the asbestos into marked bags. Of course, the workers were wearing white jumpsuits with special air masks and regulators. The bags were all weighed and then sent off to an approved disposal site.

When the asbestos was all removed, I had a contractor come in and salvage any metal from the bathhouse lockers, baskets, boiler, etc. It was quick work to demo the building bury the brick and tile in a burrow pit and place some topsoil over it. The last sight I had of that place was locking the gate at the end of the access road. Probably the same thing the mine superintendent did when he fired the workforce and shut down that portal.

It left me with an empty feeling, trying to rationalize all the manhours spent and the work that was done from that building and shaft. Hundreds of men (women weren't allowed into underground mines until the late 70s) earned a living from that hole in the ground. They were likely hired there, trained there, many probably moved up the Union pay scale from common laborer to machine operator and maybe a few jumped into a company position.

They all had to be there at that building before the shift started to change and they all left after taking a shower at the end of the shift. There were deadlines, schedules and production quotas that had to be met. The coal they produced fed the steel mills and power plants that made countless cars, appliances, and electricity to serve the community, state, or nation. Now it was all over with nothing to show for it but a mound of topsoil with some straw on top of it.

++++

The last work assignment that I had at Robena was the replacement of a natural gas line that fed the Robena Prep Plant. The Robena Prep plant was like a dinosaur, it was at least 40 years old. The sulfur-laden coal combined with the grit of the coal ash and the acidic level of the water running through countless pipes had taken its toll on this facility. It was a scary place, with massive steel beams and columns that appeared rusted through. A quick look at the condition of the facility's electrical equipment made you shake your head. Every step you made into the plant was a step of regret. The stairways were shaky, the lighting almost nonexistent, it was loud and everything shook. I mean everything. Any sane person, let alone an engineer who understood what I was seeing just wouldn't want to be in this place. But all that fear went to the backburner when the Plant Superintendent showed me the scope of work set out for me.

He started by showing me the boiler room where the main 4-inch gas line entered the plant. It fed a manifold system that led to twin hot water boilers. This plant was built before WWII, its heating system was the good old hydronic-hot water system with its cast iron radiators.

The gas line coming up out of the ground was badly rusted, it was clearly in need of replacement but so did everything else in the room. Luckily it was late summer and the gas system was at minimal use and could be shut off for a few days to make any connections. We then got into his pickup truck and drove about 1 mile across the coal yard to a corner of the property. He pointed to a yellow marker and said that's where the plant's gas line taps into the local gas company's main gas line. I asked for some site maps and he said, "Good luck". The administration building that served the prep plant was long gone and with it all the key documents. He grumbled about not having any drawings of the plant and his struggle to keep it working. As I got out of the pickup he grunted that the line needed to be replaced before the first frost, which was about 6 weeks away.

Without the internet or Google, I spent the next week or two researching how to build natural gas lines. A few calls to the gas company got me some meetings with their engineers and from there, I pretty much figured it out. They made it clear they would not touch anything beyond the metering box. A few valves, a regulator, bury everything at least 3 feet deep, use the properly rated and sized pipe and it would all be done in a few weeks. I got the bid package out and was ready to award it to a contractor. Of course, the contractors wanted to see the site before submitting anything. We met at the Robena Prep plant parking lot and essentially walked the entire gas line route. We noted that the new line route went right through a secondary but active coal storage stockpile, and he suggested that we bury that part of the line at least 6 feet deep and encase it in concrete. It was easy to imagine a bulldozer operator pushing the coal pile to go astray and dig down and tear up the gas line. That would not be a good day for anyone.

Then we started to walk over to the yellow stake where I was told the line tapped into the main line. From 50 feet away we could tell it was going to be trouble. We could smell gas and it got stronger as we walked through the knee-high grass and approached the yellow stake. At 10 feet from the stake, the smell was bad but there was a decent breeze so we proceeded ahead. We found a cinderblock root cellar-like structure with two metal doors, although we struggled, we were able to open one of the doors. Despite the fear of gas and possible snakes in our heads, we were aghast by what we saw. Inside the structure was the 4-inch tap into the main 10-inch line. But the valves, the flanges, the gas meter, and related pipe were essentially rusted through. Now I knew why the prep plant superintendent didn't drive out to the yellow stake. We left the door open and went back to the plant to meet the Superintendent.

We discussed what we saw and I emphatically stated that we had to shut the gas line down immediately. The plant manager fessed up stating he knew there were bad leaks, and also knew that there were numerous gas leaks underground along the 1-mile route.

A few more calls to the gas line company were a little revealing, they did not believe my statements and immediately sent a team out to inspect it. They found the same, marked off the area, and initiated an emergency shutdown of the main 10-inch line. Where I was only worried about the first frost they had a more significant concern of sending to shut down a main gas supply to the Pittsburgh area.

The local gas line company was swift with their repairs, which included a new meter station and tap-in isolation valve, taking only a few days to complete. By now my paperwork was in order and I had my contractor out there installing the new 4-inch gas line. They were done within two weeks; we beat the 1st frost deadline by a month.

++++

As I noted earlier, Dilworth Mine provided me with many work opportunities. One of the craziest, stupidest, and yes life-threatening assignments, occurred during a methane gas check I had to conduct at the mine. It's always the small, simple task that gets you into the biggest trouble.

Within the initial 12 months of being promoted to the Eastern Region, I found myself in the middle of a backlog of air shafts that absolutely needed to be installed, all of them ASAP. Of course, these multi-million dollar projects required permits, engineering work, and a bidding process to select the various contractors. Plus, plans and contracts had to be put into place to bring electrical power to these fan sites, which typically would have a 1000hp motor and usually a 2-3 MW underground power supply borehole. The time frame needed for getting these heavy-duty power lines to these remote locations was usually the critical path.

The very first airshaft that I constructed was for the Dilworth Mine. It created many experiences and memories for me. But it's only a side project, to the event, that would turn out to be one of the most dangerous experiences I ever experienced underground.

++++

Almost a year later while in the middle of constructing the Dilworth # 6 Air Shaft, I became aware that the old works section of the mine were losing the positive flow of air or ventilation through them.

Having strong positive ventilation through these old works was a requirement of the Federal Mine Safety law. The old works at Dilworth were a collection of entries, cross-cuts, and retreat-mined areas that were mined 10-20 years earlier. The old works were an isolated block of coal about 2 square miles in area, just off the "haulage mains" that served the rest of the coal mine.

These old works had two sets of entries that intersected with the mine's mains, one set of entries received fresh air (fresh from the surface) that fed into the old workings while the other set drew out the bad air, aka methane-laden air and dumped it into the mine's existing return airways.

The return airways fed an exhaust fan which would dispel the air to the surface. Over time, the old works would cave in and fill up with water and the passage of fresh air through this area would get harder and harder. There were two solutions to this problem. Permanently seal off the section of the mine or drill a hole into the farthest part of the workings and let fresh air enter from there. The latter was the typical practice in the industry and usually solved the issue. So the cast was set, I was charged with drilling a ventilation hole, a 9-inch diameter hole, into the back end of the old workings.

Heck, no problem, I was on the job just over a year and I had drilled numerous holes of this size and depth. So I bid it out and had the contractor lined up within a month. There is an MSHA regulation that states, prior to a drill bit penetrating an active coal mine the area must be inspected and methane level readings taken. I had to find a way to inspect the area where the 500-foot deep borehole would penetrate the mine before the drilling bit punched through. The classic cliche "easier said than done" comes to mind.

After a few weeks, the borehole was down a few hundred feet. Timing was critical, we had to inspect the area exactly one shift prior to the drill bit busting through into the mine. As an extra precaution, the Superintendent and I decided to make the punch through on a Sunday, when only 5-8 workers would be underground in the mine.

I had finalized the arrangements for a Foreman to go with me underground and perform the methane pre-check that day. If all went well the driller would punch through the next day (less than a shift later).

I was up at 5 and out the door shortly thereafter, into the dark February moment. It was a cold Sunday morning, a very cold morning, something hovering around zero. As I climbed into my pickup truck, I was thankful that the temperature in the garage was probably in the teens. My pickup truck was just beginning to produce some heat when I reached the Regional Office and switched to the ice-cold company truck. I shivered for the initial 30 minutes on my way to Dilworth. I arrived at the mine by 7:30, to meet up with the Superintendent and the designated Foreman who would accompany me on this trip underground.

The three of us met up with the Mine Engineer and looked at the old works map and plotted our route from the mains through the old works to the proper intersection. It was rare to see the Superintendent and the Mine Engineer on a Sunday. They all usually worked 10-hour days 6 days a week, they could not have been pleased to be at the mine that day.

After it was plotted on a map and a copy made for us, the Foreman and I stepped into the bathhouse part of the portal. He asked me if I wanted to put my wallet in his locker. I said, "No need, I always take it underground". He replied in a straight voice, "I really think you should, we are going to get wet today".

That stopped me in my tracks. In all my mining experiences I have heard many phrases, "low oxygen, bad roof, stray electrical currents, high methane, tight entries, or no airflow, but nothing would raise a miner's danger antenna, more than the words, "You will get wet". Especially since I had not prepared for it, I had not put on an extra layer of clothes or brought a spare set of clothes for the return home. I tried to rationalize that it wouldn't be that bad, that the temperature underground is typically a steady 50-55F. I hoped when he said "get wet" he meant just our legs but watching him tuck away his wallet into his locker and then remove any remaining material from his other pockets, I knew the water would be at least waist high. Oh well, I thought it was too late to turn back, I gave him my wallet and truck keys.

Putting on the miner's cap lamp and battery was a little more difficult than usual, the in the battery-lamp area was in the single digits, I had to put on my gloves to handle the metal battery case (otherwise my skin would stick to the metal). The cord from the battery to the headlamp was as stiff as a piece of conduit. It was cold, really cold, I wanted to get underground as quickly as possible.

The ride down the elevator was cold too, just the Foreman and myself. The clouds from our breathing seemed to hang in the elevator just above our heads. We hit the bottom and headed to a jeep on a side track. Again, it was cold, 0 degrees or lower, the fresh air coming down the airshaft was whipping past us and cutting through our jackets, shirts, pants, and gloves. It's at moments like this that you recall and understand the meaning of the wind chill factor.

We climbed into the jeep and headed to the old works. The old works were about 3 miles from the shaft bottom a good 20-minute ride in the jeep. It wasn't until we were about 2 miles away and switched off the main line to a sub-main that the temperature got up into the 40s maybe 50. The warmth was a good feeling, like stepping up to a fireplace in a log cabin. We arrived at our designated spot, parked the jeep, and looked at the map of the old workings one more time.

We quickly found the cinder block stopping with the 30-inch by 30-inch metal man door that led us into the old working. After trekking past a few cross-cuts and entries and crawling through a few more man doors we reached the old works. Surprising to me they weren't that old, they were in pretty good shape, at least for the initial couple of hundred feet, the floor was not heaved, the ribs of the pillars showed no sign of sloughing and the roof was in great shape. The air wasn't damp or musty, which is typical of the many old works I had traversed in my past. So I was a little surprised that the mine management had claimed that the area was not getting enough fresh air and asked for the vent hole. But that was the end of the good news.

A few steps later I heard it, the squish sound of my rubber hard-toed boots stepping into the water. Initially, the water was in pools or puddles that could be avoided, but after a few hundred feet it became a steady one-inch-deep pond. I had gotten wet underground before from working on pumps but I had never been standing in a pool of water that filled the entryways and crosscuts.

It was interesting how our headlamps glimmered off the water and helped light the way forward. Much different than the normal walking underground where the dark gritty matter on the floor, walls, and roof absorbed every photon of light. After about a mile (or 50 blocks of coal), we were halfway there. The water had risen but it had not gotten above the edge of my boots. I found myself clinging to the coal ribs, where some sloughing of coal from the ribs allowed me to gain a few inches of elevation to keep the water from getting into my boots.

The Foreman who carried the mine safety lamp just laughed at me as he plodded through the water making waves big enough to counter the meager elevation gain I had. He was cut from the standard Mine Foreman mold. About six foot two, over two hundred and fifty pounds with a beard as well developed as his beer gut. He looked like the brother of the Mine Superintendent. It was clear that the less said the better, I knew that complaining would not be tolerated.

After another hundred feet I realized my efforts were futile, and I too plodded into the water. I immediately realized why I was avoiding the plunge, the water was cold, maybe it was the same temperature of the air around 50F but the 48-degree difference with my body temperature made the water rushing down my boot feel like a pitcher of ice water. We plodded forward at a much slower pace.

Much faster than I would have wanted, the water reached our waist, we paused and looked at the map that I was keeping in my breast pocket. We got our bearings and realized we had another half mile to go. We also realized it had taken about two and a half hours to traverse to this point. We figured we had another half hour to get to the designated point. At that point putting us underground for three hours.

If it took that long to get back to the elevator shaft we then would be back above ground after 6 hours. The Foreman said it would make for a short shift for us and maybe we could get home at a decent hour. But my head thought of a different timeline, I was thinking we would be in cold water up to our waist for over two hours, maybe three. To say it concerned me would be an understatement.

The next half hour was absolutely one of the worst of my life, as we plodded forward, the water rose above our waists. This meant that over 50% of our bodies were submerged in the cold water. There was a noticeable change in comfort and also core body temperature. We have all walked across a swimming pool with water up to our waist and know how it restricts your legs and foot movements. Add on 10 pounds of clothes, a miner belt with battery, steel-toed boots, and a 5 lb. self-rescuer and it just makes it more fun, or what I would call an extreme cardio workout. The effort and the cold were exhausting.

The rise of the water did not stop at our waist, within a few hundred feet it reached our chest, at this point I put the electronic methane detector under my hard hat. The Foreman was struggling to keep the mine safety lamp above the water. After another 10 minutes of plodding forward, the water reached our collars, with the water just below my chin I finally spoke up and said, "Let's stop and get our bearings".

We stopped for a moment, and that's when I realized I forgot to move the map from my chest pocket to my hat, the map was soaked and ruined. To the novice miner, panic might have ensued, but we both knew we had long ago given up on the map and we were forging ahead on the mental pictures we took of the map. With my chin just a few inches above the water I was about to say, "This is good enough let's take the air readings here and head back". The Forman must have been reading my thoughts, and said, "We are almost there just a few more blocks to go". I didn't complain or state my belief that taking an air reading here or one 200 feet from here made any difference.

But I did say, "You do realize that if you stumble and slip under the water, there is no way I would find you", he paused and turned to look at me. Before he could respond I replied, "I'm just saying if you twist your ankle or knee you are not getting out of here, there is no way I could drag your butt through this water". There was no reply, he just turned his head and plodded further on into the mine.

A few steps later he took off his hard hat and placed the miner's lamp in and floated it along with him. Yes, this was now getting ridiculous. A few more steps and he too realized that he had reached his limit, he turned to me and said, I think it opens up a bit a little further up, let me go up to the end of the block and check it out. It was a welcome relief that he was considering stopping, but I didn't like the idea of us separating even if it would only be 50 to 100 feet. So I tagged along, albeit at a slower pace and the gap between us widened from 20 feet to about 50. He was right the coal seam had a small elevation change in it and we found ourselves in water only up to our chest. He proclaimed this was enough and looked at the flame in his safety lamp and said there was no methane.

I took out my electronic canary from under my hard hat and took readings of the methane and oxygen levels, both were good. With no time to pause or think, we immediately started to head back. It only took a few minutes but the adrenalin and testosterone that drove us to this point wore off. Although I felt the cold water when it initially filled my boots, and then again when it reached belt-high, I had forgotten about it for the last 20 minutes. At this point I could feel my body losing heat, maybe it was the adrenaline that had increased my metabolism, but for whatever reason, I was now getting cold, and I knew we were more than an hour and a half away from getting out of the water!

When we were back in the area that required the Foreman to float the mine safety lamp in his hard hat, I began to think about the water level and whether it was rising. I recalled that when we walked into the water it was flowing in the same direction we were walking towards. If it was flowing towards us the level would be rising and some of the areas that we walked through would have higher water levels! Ahh, just more fun! I didn't want to think about the worst-case scenario, that if the water had risen so high that we would be blocked and couldn't get back out. There was no time to dwell on such an issue, just move on.

It took about 20 minutes but we eventually got back to the area where that water was below our chest, and another 20 minutes before it dropped below our waist. The one good aspect was that with the decreasing level of water, the resistance to walking was getting less. It brought a little bit of enthusiasm to us, our speed picked up, and that helped raise our body temperatures and my morale.

After another 20 minutes the water level dropped below our boot edges, but since there was no dry spot, no chair, and no bench to sit down on, we had to walk another 10 minutes before we found a dry spot, a little elevated island where we could stop and pull off our boots and empty out the water. It was good to get off our legs for a minute, but that was it, just a minute. This brief stop made us realize how wet we were, we were drenched, and soaked, our clothes now weighed three times more than when dry and we no longer had the buoyancy effect of the water.

I mentioned that I felt drained, and surprisingly the Foreman agreed. With words of encouragement, he said "Kid it's likely to get tougher, but let's focus on getting to the man-doors". We both struggle for the next 15 minutes to get to and through the man-doors. The weight of the water-laden clothes, loss of body heat and just being underground for 5 hours were taking its physical toll. The slower pace clearly lowered my metabolism and I was cold, a different kind of cold I had never felt before. I grew up in Northeast Pennsylvania so I had been exposed to temperatures below zero and recalled the time I made a two-mile trek to our home in single-digit weather, but this was different. Every part of me was cold, not just my fingers, toes, or face, I felt like I was losing my core body temperature.

We got to the last man door; we knew the temperature on the other side would be at least 10 degrees colder. We stopped and discussed our options. We could strip down and squeeze out the cold water, but that would take time. We also knew that in the jeep we had our coats, lunch pail, and dry gloves. We also discussed that as we got closer to the shaft the air would get colder, very cold. We both knew the high temperature for today was not going to break 30F and that it would be a twenty maybe thirty-minute ride to the shaft bottom with a 20-30 mile per hour wind in our face. Lastly, we also knew there was a radio on the jeep. We discussed in as simple terms as possible, that time was not our ally. We agreed to forgo draining our clothes, get to the jeep as quickly as possible, and head back to the shaft bottom. Once we reached the mains we would stop and radio in to get clearance to the elevator and also tell them we would likely need help at the shaft bottom.

We reached the jeep and quickly grabbed our jackets and flung them on, gloves were next. I positioned myself in the jeep to minimize any airflow over my body, crouching low in a flat position. The Foreman sat in the driver's chair and placed the harp on the trolley line. I thanked god that the juice flowed and fired up the electric motor and the jeep's lights. I was so cold I thought I could feel the warmth from the jeep lights, ridiculous, yes, but the yellow glow of the jeep light was a reminder of warmer times.

It took only a few minutes before we hit the mains and radioed in. The main line was clear all the way to the shaft bottom. The dispatch asked why we might need help at the shaft bottom, but he didn't reply. The dispatcher understood his silence, namely that we had a serious matter at hand and that no one else in the mine needed to hear about.

The next 15 minutes of my life were brutal, with the jeep moving at 10 mph and the intake air rushing at 20 mph it made for a 30 mph wind in my face, my feeble attempt to shield my body from the wind was just that, feeble. It had no effect. After about five minutes, I started to realize that my clothes were freezing in front of me. I knew that I had to keep my feet, hands, and face muscles moving to maintain some circulation and keep them from freezing in place. At the same time, my jaw and teeth started to shake, not from the movement of the jeep across the rail tracks, but from the cold. It started intermittently, and within a few minutes, it was uncontrollable chatter.

A few minutes later I began to realize my hands, my toes, and my neck were getting stiff, real stiff, it took all my effort and concentration for me to turn my head and check on the Foreman commanding the jeep. Thank goodness he had a heavier coat, thicker gloves, and more body mass. I figured we had 10 more minutes to get to the bottom. And I was sure when I got to the surface I would have frostbite or worse on my toes, hands, and probably my face.

I tried my best to move my fingers and toes, but I realized I was having trouble just concentrating. A fear set in that I might pass out so I focused all my energy on staying awake, counting in my head, and like any good engineer doing square root calculations. At about the point that I was ready to close my eyes, I was sharply shaken by the jeep cutting off the main line and onto the side track for the shaft bottom. The jarring movement, the squealing sound of the metal wheels grinding against the rails and the sparks from the jeep's harp bouncing off the trolley wire kept me from passing out. A couple of more spine-jarring turns confirmed that we were close to the shaft bottom. The squeal of the brakes and the jeep coming to a stop brought some mental relief to me. The elevator, warmth, heat, was but a few dozen feet away.

Honestly, I don't remember much of the next 10 or 15 minutes. I vaguely recall some miners dragging me and the Foreman out of the jeep and into the elevator. The next clear memory I have was of me lying in the bathhouse, being flooded by the shower and mumbling "please turn off the hot water it was stinging-scalding me".

A few minutes later I could see the Foreman sitting across from me with a shower on him too. I struggled to my feet and reached to turn off the hot water, only to realize it was not on! I was being showered with 60-degree water yet it felt hot or rather stung my face and hands. The shower room was one big cloud of steam. False steam from the shower spray hitting 30-degree air. There were icicles hanging off the other showerheads.

As I stood up, I realized I was still in my mining clothes, jacket and all. I grabbed the shower handles and turned the hot water on, slowly the water, my clothes, and my body warmed up. The warmer water turned the shower room into a full fog, steam bath. It felt good, really good, to breathe in that warm moist air. I began to realize that my hands and fingers were all ok. I wiggled my toes and pressed them all against my boots to make sure all ten were moving. I was a happy man.

About 30 minutes later I was putting on a borrowed pair of pants and tee shirt. As I was wringing out the water from my clothes the Foreman handed me my wallet and car keys. We gave each other a smile and nod and he was off to his truck. I wasn't that far behind.

As I exited the portal doors, the cold air hit me hard, I hadn't realized that it was late, past 7 and it was pitched black, we had been in the mine for over 10 hours! I jogged to the back end of the parking lot and got into the company truck. I knew it wouldn't warm up for 30 minutes, so I pulled it up to the portal door, got out, and left it running with the heater on full blast. I found the vending machines and had my dinner of a Snickers bar and a can of Coke.

I got back to the house around 9 pm, I dumped my wet clothes right into the washing machine. I was very tired and just wanted to get to bed. But once I got up to the master bedroom, I knew I needed a long hot shower in my own bathroom. I put on some long underwear, a tee shirt, a pullover, sweat pants, thick socks and crawled into bed.

The next day at work was uneventful, I went back to Dilworth to check on the drilling rig to see if it broke through into the mine. I got home at the normal time, just before dinner. I started the washing machine. After dinner, Tammy put the wet clothes into the dryer.

Later that evening I realized I had a burning feeling in my groin area, hands, feet, and armpits. As I got changed for bed, I realized that my skin was exfoliating, after a closer look at my arms and legs I realized my whole body was shedding a dead layer of skin. Two days later, my feet and hands were pretty raw, and those places that didn't see the sun, were painful.

Tammy went to start a load of laundry and pulled out the clothes she had put in the dryer a few days earlier. She laughed out loud and walked over to me with my long underwear in her hand. Typically they are a faded white, but what she was displaying in front of me was a bright orange, pumpkin color. "So what happened here?' It was obvious, that the water I had been submerged in was laden with iron and surly had a slight acidic pH value. Thus, the orange-colored underwear, and the resultant skin defoliation.

Eventually, the redness across my body disappeared, but not the memory.

| Author Notes |

Warning - This is a Novella (not a short story and more than a Chapter in a book). I wrote this with the mindset of explaining and providing details not typically seen in stories. In a way, I hope it is educational as I tried to describe the details of underground coal mining and power plant construction/operations. I lack professional training or writing experience. I hated my HS/College English and literature classes. My passion has always been engineering, with a focus on numbers, formulas, equations, and algorithms. Thus, the two Engineering Degrees. Somehow I obtained some management-people skills that helped me climb the corporate ladder. All of my stories are based on actual events, of course with a just a touch of embellishment.

|

![]()

By CM Kelly

"... Sparks Flew From My Mechanical Pencil ..."

It was 1989, I was 31 years old, it had been 9 years since I graduated from Penn State University with my Mining Engineering Degree, I had my Master's Degree from the University of Pittsburgh and my Professional Engineering license. Married for four years, we built a homestead on 10 acres and we just had our first child. I had just been promoted to the Chief Mining Engineer at the Bailey Mine Complex. This was the 4th promotion in nine years at Consol. With degrees and licenses all having fallen into place, I believed I was pursuing the American Dream and well on my way up the corporate ladder.

I had spent the previous four years as a Regional Engineer working on various capital projects and mine planning activities within the Eastern Region of Consol Coal Company (Consol). The Eastern Region was made up of six underground mines and one surface mine, all but one were union mines. Eastern Region encompassed an area from Eastern Ohio, through the West Virginia Panhandle and up into Western Pennsylvania. Consol was the 2nd largest coal company in America, as measured in both tons produced and revenues. Consol's mines were primarily in the Appalachian coal fields, spread throughout West Virginia, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, with several surface mines in Illinois and Ohio, and two mines west of the Mississippi.

Bailey Mine was the jewel of all jewels in the coal mining industry. It was opened in the mid-80s with much fanfare. There was some industry backlash due to its opening during a period of oversupply of Appalachian coal, a time during which the steel mills around Pittsburgh were shutting down, and when massive nuclear power plants were pushing out the traditional coal-fired power plants. But the primary reason for the special attention from the industry, and to some degree the nation, was because it was a non-union underground coal mine. Bailey Mine was initially projected to be a massive 3 million ton per year mine almost 50% larger than any underground mine in Appalachia at the time. It would be the first non-union coal mine to open in the heart of the United Mine Workers of America ( UMWA).

The Bailey Mine was located in Washington County, Pennsylvania, about 50 miles south of Pittsburgh and just a few hollers from the West Virginia border. Unlike most coal mines throughout the Appalachians, it was not located near the Monongahela, Alleghany, or Ohio Rivers, landlocked it was forced to ship its coal by a new rail line spur.

The mine was a direct threat to the UMWA's current members and essentially its future. There could be no doubt by anyone working on this project that for Bailey Mine to succeed it had to thwart the UMWA. It was firmly believed within the halls of Consol's Corporate Headquarters, during these Reagan years, that unions no matter what the industry, were dragging down economic growth and thus the middle class. With their ever-increasing dues, featherbedding and generally unproductive work ethic, many industries across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic had been migrating south towards non-union working environments and lately, they were not stopping at the US border as they moved their factories to Mexico, Brazil, or SE Asia.

Interestingly, the UMWA never publicly came out and challenged Consol's investment in Bailey Mine as it was being developed and going through the permitting process. Rather the union took the position that under the Fair Labor Act, they would let the mine get built, let Consol make the $100,000,000+ investment, and once it was fully staffed they would petition the workers and call for a union vote. Their confidence lay in the fact that Western Pennsylvania was swamped with unemployed UMWA workers. Thus, the hiring pool that Consol would draw from would have a built-in bias towards the union. In their minds, it was the proverbial slam dunk.

But, as many best-laid plans have gone in the past, the cards did not play out as planned. The Union's labor pool logic, in fact, worked against the Union. Consol's management invoked a policy of only hiring coal miners who had been laid off for at least 12 months. This policy assured them of a "hungry" workforce, a workforce that would literally work their butts off to protect their higher-than union rates-paying jobs. Essentially they were hiring an employee base that had been fed up with the work outages, strikes, and union dues that the UMWA was known for.

After several years of environmental permitting and two years of construction, the Bailey Mine Complex was up and running. From the onset the mine was setting production records; most tons per day, most tons per week, or most tons per month. There seemed to be a steady banner of congratulatory press releases during the initial months of operation. No doubt these press releases were rubbing it in on the union.

The mine was blessed with a great coal reserve, a 6 to 7-foot thick coal seam with a solid-consistent roof, a level-dry floor, and nominal methane gas trapped within the eon's old coal seam. With two modern, highly efficient longwall units and the advantages of an all-conveyor belt haulage system, the production cost was a fraction of the union-controlled mines within Consol's fleet.

The bean counters and executives were quick to recognize that the differentiating issue between the Bailey Mine and the other mines in the Appalachian Coal Basin, was primarily driven by the labor force. At first, the high productivity results were discounted as being a result of the new equipment, the two longwall layouts, or even plain old rookie luck. But after a full year under its belt, the productivity figures continued to improve. More coal with less manpower and the same capital investment translated into lower production costs, which quickly fell out to the bottom line as higher profits.

Within Consol, upper management began to recognize that this was not an aberration, a short-term phenomenon, the high risk of opening a non-union mine was paying off like no other investment in the company.

Not that a great return on investment wasn't a worthy goal, but there was a bigger prize being sought, and it was a game changer for the coal industry. The lower production cost allowed Consol to lower the price of the coal it sold while maintaining an exceptional profit. Of course, many with an MBA could play with this concept and try to determine the optimal profit level, but Consol's management had one other objective. Namely, it wanted to shut down its high-cost/low-productive union mines in the Appalachian Coal Basin and move those coal sales contracts to Bailey Mine. A strategy to drive the industry as a whole away from union labor.

With the higher productivity rates the mine's annual production was on a constant path upward, after 2 years of production it had increased from 3 million tons per year (mtpy) to 4.5 mtpy. A phenomenal 50% increase in production from the same capital investment. Management was extremely proud that these increased production levels were from a workforce of about 3/4th of the initial estimated workforce. Put another way, the original economics were based on a 3 mtpy production rate, a $100 million investment with 400 workers. In actuality, it was producing 4.5 mtpy, (50% more), with 300 workers, (25% less) and no additional capital investments. Around the water coolers within Consol, it was being whispered that every day Bailey Mine brought in a million dollars (over $3M in today's dollars)!

Over the next 2 years, the Bailey mine's productivity rates continued to ramp up. By 1988 it had achieved a production rate of 6 mtpy, again with essentially the same equipment and a slight increase in labor, inching up to 325 workers. These gains were not without a little wear and tear on the mine's management. The salaried staff was being stretched thin.

As a Regional Engineer, I had several construction projects at Bailey Mine. Whether it was with conversations with workers underground, or in the bathhouse it was not uncommon to hear the salary Foreman or Supervisors claiming they hadn't had a day off in 2 or 3 months or were working 12-14 hour days for three or more weeks at a stretch. However those mumblings were just a whisper compared to the bravado, or some would say arrogance, that the management and miners at Bailey extolled.

They were justifiably proud of their accomplishments; they were by all standards the best coal miners in the US, if not the world. It created a culture, some outsiders would say an ego, at the mine that "they were the best of the best". For the most part, this was positive, but occasionally it would grate on the newcomer or the person who tried to present a new idea to the mine.

After achieving the 6 mtpy mark and staying flat for almost a year there was a building consensus that the mine had peaked. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year mine forecasts were showing that to maintain the 6 mtpy rate additional capital and substantially more workers would be required. This was due to the fact that the active mining face was getting further and further from the main shaft where the workers portal-ed in and out of the mine. The jewel of Consol and the Industry was big and bright, sitting strong on top of the mountain, but it was beginning to lose a little of its luster. By all standards, after 4 years of operation, the mine and the investment; were all a success, one that far exceeded even the most optimistic estimates.

Bailey Mine clearly had set the bar within Consol, and as the execs had hoped, throughout the industry. Its economic impact was far-reaching, more so than just within Washington County. The production above the initial design rate allowed Consol to shut down a least a half dozen of its "less productive union mines" in the Pittsburgh Coal Basin. This was not lost on the UMWA and when the UMWA contract came up for negotiations the union was upset, hot, yet on their heels.

The results from the Bailey Mine gave the coal industry negotiators, headed up by Consol's CEO Bobby Brown, much more negotiating leverage. Resulting in dramatic changes in the work rules. The union leaders, being led by a young, outspoken lawyer from Western Pennsylvania named Richard Trumka, (yes Richard Trumka, the ex-president of the AFL-CIO) did some face-saving by obtaining a very favorable pay rate increases. But the union was now wise enough to see the future and the future was spelled with a capital C, to survive in the upcoming 90's the union card-carrying members in the coal industry had to be competitive.

Bailey Mine was such a success that plans to replicate it with a twin or sister coal mine were being executed. The 2nd mine would have its portal and production slope located just a few hundred yards to the south of Bailey's. The existing prep plant would be expanded and it would use the same rail loadout facility. Development of this new mine started in 1988 with the submittal of the necessary permits. No doubt sending another serious message to the UMWA.

****

The coal reserves that were dedicated to the Bailey Mine were part of a detailed plan that called for four 3 mtpy mines, together pushing out a phenomenal 12 mtpy. With Bailey Mine doubling the initial forecasted annual production the plans were quickly revised to reflect just two 6mtpy mines.

By early 1989 all the permits were in hand and construction on the 2nd mine commenced. The new mine was called Enlow Fork to reflect the name of the nearby creek.

Due to some favorable compensation loopholes that were created between the two mines, a portion of the Bailey Mine management jumped over to Enlow Fork. This shift in personnel resulted in the Chief Mining Engineer at Bailey, the person who had a hand in the mine's outstanding results, leaving Bailey Mine and joining the Enlow Fork team. This opened up the position at Bailey Mine to which I was promoted.

I was not a stranger to the Bailey Mine, its workers, and its key managers. As a Regional Engineer, I had put in numerous degas holes, plugged several abandoned oil wells, put in two air shafts, conducted numerous underground ventilation surveys, and most importantly was doing the long-term planning for the mine, creating 1, 3, and 5-year production and quality forecasting mine plans.

Typically all the forecasting of the coal quantity and quality, both short and long-term, was done by the Chief Mine Engineer at each coal mine. But in the Eastern Region, due to my computer background (I had essentially earned a minor in computer science at PSU), I created a computer program that greatly reduced this manually intensive planning effort.

Creating mining and quality forecasts for a coal mine is like playing three-dimensional chess, but with one additional element, time. Essentially it involves all four aspects of the space continuum: height, depth, width, and time.