![]()

By Jay Squires

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Juniper Albright: Seventy-six-year-old woman who was Fanny’s former companion from their first years at Brady City.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times; now in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair CENTER, and front steps behind, descending to street level with a flowerbed to the side. UPSTAGE LEFT, is like a separate SET placed at an angle to the main stage with indistinct, smoky walls (conveying a sense of unreality). A very plain cot faces DOWNSTAGE. This section is always in shadow when downstage is in full light—and vice-versa [Remember this is from the actors’ perspective, not the audience’s. What is “left” to the actor would be “right” for the audience. What is far back on the stage to the audience is designated “upstage” to the actor.]

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, Aug. 8, 1929

AT RISE: FANNY sits in rocking chair facing REPORTER. She is wearing a flowered housedress and he is wearing a suit with the tie loosened at the neck and askew, a hat on the floor beside him. JUNIPER sits on the cot, in shadow.

FANNY:

You might as well hear it from my mouth, young man. This face sure ain’t gonna hide it none. I’m eighty-five years old. Back in my sixties, when I looked in the mirror I saw a forty-year-old woman smiling back. Now I cain’t even find the mirror without my specks.

[The young REPORTER smiles genuinely, then scratches a spot above his right ear. FANNY watches this, then looks above his head, a slight smile lingering on her lips]

[Stagelight dims on FANNY and the REPORTER, and falls full on JUNIPER, sitting on her cot, the letter held in both hands]

JUNIPER:

(Reading)

Well, I watched him smile, sweet Juniper, and scratch a spot just north of his right ear. Now, I know you always want me to get to the point—and I know they only give you a few minutes for letter-reading time—but if I don’t get the details right, it’ll all just flutter ’round like a butterfly on this dried up field of my memory till it can’t find a fresh flower stalk to light on, and it’ll be gone. So, yes, the place he scratched was just north of his right ear. Then, I said to him:

[Full light on FANNY and REPORTER, while JUNIPER goes into shadow. NOTE: hereinafter stage directions will be shortened to “Switch to”]

FANNY

Hells bells, son, don’t bother now sayin’ how wrong I am—how I’m still a charmer! It’s too late. Your timing’s way off. If mine’d been that bad I wouldn’t’ve lasted so long at the Tavern. And you wouldn’t be here now interviewin’ me.

REPORTER:

That’s right. Forty-four years!—It’s hard to imagine? Tell me about that, Miss Bar-Barn … um, Miss Barnwarmer.

[Switch to:]

JUNIPER (Reading):

I wait for him to finish tussling with my name. Then I smile at him and I say ...

[Switch to:]

FANNY:

That’s how it all started, you know. With the name.

REPORTER:

What do you mean?

FANNY:

That first night. Back in eighty-five. Juniper and me, we was sittin’ at the table in Hazel’s Tavern—that’s what it was called before she shortened it to the Tavern. A couple of unescorted ladies, sittin’ in a man’s bar.

REPORTER:

(Writing on his tablet)

Your friend … Juniper’s her name? J-U-N-I—

FANNY:

P-E-R- yep, we was travlin’ companions. Sisters, we’d say if’n it ever came up. You could say we was more grit than brains. But the stagecoach left us thirsty and besides, Juniper wanted Brady City to know we weren’t plannin’ on leaving any time soon.

REPORTER:

Why was that, Miss Barn—warmer? Brady’s not a big city even now. But back then—

FANNY:

There was close to a hundred. But outta that hundred was one … Thurston Flourney!

[With the name “Thurston Flourney” the REPORTER is seen writing intently on his tablet]

[Switch to:]

JUNIPER:

(Reading)

Juniper, I watched that young man write that name down just as quick as I said it, then underline it, not once, but twice. And before the day was done, he had it circled. Oh, I tell you, love, he was a reporter, true to his story.

[Switch to:]

REPORTER:

(Tapping his pencil on his tablet)

So, Thurston Flourney—You’re saying that’s the name it all started with?

FANNY:

No … an’ you’re gettin’ ahead of yerself. I cain’t believe your editor sent you fifteen hundred miles to write a story ‘bout Thurston Flourney.

REPORTER:

No, Ma’am.

[Switch to:]

JUNIPER

(Reading)

Just then, I watch the color leave his face like a south-goin’ bird in winter. I think he was afraid I’d send him away without his story.

[Switch to:]

FANNY:

Then get your pencil ready again, and listen. Juniper an’ me was at the table. I had my sarsparilla and Juniper had her shot of whiskey alongside a glass of water. A couple of fellas walks up to our table an’ one of ’em flattens his hands on it and gets up real close.

(Hunched forward, her hands on her knees,

elbows out, her voice takes on a deeper, more

threatening tone as she acts out the character

in her story)

He says to us, looking from one to th’other, ‘Think yer mama’d approve you bein’ in a ’stablishment like this—two little things like you? What’s yer names?

(Beat)

Well, Sir, Juniper just stares at him, like a rattlesnake would afore it struck. I knew I had to say somethin’, and quick. I was just hopin’ he couldn’t see my heart poundin’ through my dress, cause he sure was lookin’ hard enough at where my heartbeat was comin’ from.

REPORTER:

(Animated, a slight smile)

Okay … yes ...

FANNY:

I says, ‘Sir, my name is Fanny—Fanny Barnwarmer.

(Sitting up straight, holding up a finger

to REPORTER)

You see, son, it’s all in that timing I talked about earlier. I wait till the timing was just right and I tells ’em —now remember, there was only about ten in the bar back then—and so I says right through that curtain of bad breath … and it was baaaaaad—

(Suddenly, leaning in again toward the

REPORTER)

I says, ‘Now, I ask you, Sir, who’s gonna saddle a pretty little thing like me with the name Barnwarmer?’

(Beat)

Now I gotta interrupt myself, Mr. Reporter, cause this next part’s very important—details, details—but just as soon’s I says ‘pretty little thing’ I let drop my right eyelid, not like a flirty wink, but like one o’ them curtains ya pulls down over a window—like this …

(Demonstrating)

[Switch to:]

JUNIPER

(Clearly showing her emotion, stopping

her reading now and then to stare off in

space)

Juniper, Darlin, I wish you coulda seen his face when I did it! His laugh came so sudden-like when I dropped my eyelid, that he, hisself, lets go his pencil and he had to get up and fetch it from where it rolled to, off the porch, and into the flower bed …. Oh, I know, sweet Jun, how you hated that look, 'specially when it came to be a part of my act. You thought it was a cheap trick, and made a clown of me and all … and was disrespectful. For a woman, I mean. Sometimes, I’d catch the look on your face from my one open eye as you was sitting where you always did in the audience—I miss you sittin’ there, Jun. Nowadays, I insist that table be always empty now, but with a whiskey and water glass aside it—Anyhow, I know how my clownin’ around pained you. But it worked, Darlin. It worked! …. Anyways, once the reporter got his pencil and settled a bit I went on ….

[Switch to:]

FANNY:

So after I raise the curtain on my one eye and then look at them so innocent-like, I says, ‘I ask ya, kind Sir, who’d saddle me with the name Barnwarmer, and then plop a first name like Fanny on top of it?’ Well, he stood straight up, and he looked at the other fella, then looked back at me, and then he let out a guf-faw that came all the way from his gut, and the two start laughin’. And that goes on for near-five minutes, while I keeps a straight face.

REPORTER:

I’d like to have been one of those ten who were in there, just to lean back against the bar and watch you perform.

FANNY:

Turns out the fella’s sister was Hazel. Now, he may o’ been no more’n a turd in the hen house full ’o turds, but his sister—ah, well, sir, she was one sharp Gal. She knew if she’s gonna make Hazel’s Tavern a respectable success, she’s gotta draw families in from miles away. That you do through entertainment … an’ advertisin’.

REPORTER:

And so he tells her about you?

FANNY:

It happens she’d been keepin’ an eye on her brother all along to see as he didn’t get hisself in any trouble. So she saw what I’d done. Then, after he stops laughin’ he goes up to her and I see him pointing at his eye and tryin’ to do what I did. He’s tryin’ to hold his eyelid down with his other hand, and I see they’s both laughin’ by now.

REPORTER:

Well, it is funny, Miss Barnwarmer. It was kind of a one-liner and a sight gag, wasn’t it? Like on vaudeville. But still, it’s not an hour and a half performance, is it?

FANNY:

(Pauses, as to study him)

No, it ain’t. So she buys Juniper a whiskey an’ me another sarsparilla and she plops herself down at our table. She asks me if I knew I had a knack for makin’ people laugh. I tell her people usually come around to laughin’ if I talk long enough. For some reason that makes her laugh. She asks about Juniper and me’s stagecoach trip from Springfield to Brady City. And she laughs some more. Afore I finish my sasparilla she’s offerin’ me two dollars a night, twice a week, just to talk to the people. And that, young man, is how it all started.

REPORTER:

I can’t wait to see you perform tonight.

FANNY:

Well … It’s a differnt Fanny Barnwarmer you’ll see tonight. Back then I had my legs. And some would say …

(With difficulty, bending to raise

her housedress to just above her ankles)

they was mighty fine legs. Now they just cross at the ankles underneath my rockin’ chair. Up till five years ago, the stage curtains would open and there’d be only the rockin’ chair on the stage. And I’d come from the backstage side carryin’ my newspaper in one hand an’ my specs in the other. Now, I’m sittin’ there, my specs on an’ the newspaper unfolded in my lap. But when I open my mouth, young man—well. Forty-four years! And things just keep gettin’ better. You know why?

REPORTER:

Tell me.

FANNY:

Because the world just keeps gettin’—crazier. An’ it’s all right there in the newspaper. The good old Brady Sentinel. There’s nothing I cain’t find to talk about that ain’t in the Sentinel.

REPORTER:

(With a small shake of his head, and a

skeptical look on his face)

Is that a fact, Miss Barnwarmer?

FANNY:

That is a fact, son.

(Her head tilts, and she seems again to

study the REPORTER)

I been startin’ out my act like that at the Tavern since the get-go. But listen … you been squirming round your chair like you got more to say, but you jus’ don’t know how to say it.

REPORTER:

It’s just that—Ummm … Well … there was someone, the name of Will Rogers, who got very famous saying that. He said, “All I know is just what I read in the papers, and that’s an alibi for my ignorance.”

FANNY:

I have heard the young fella’s name. I’ll give you that. I’d have to check Hazel’s logs.

REPORTER:

Her logs?

FANNY:

Up till she died, ten years ago, everyone who bought a ticket for my act had to sign the register, including their address. She’d use it in advertisin’. Said it was good for business.

REPORTER:

I’m not sure I understand. You’re saying Mr. Rogers …?

FANNY:

Mighta been. Might not o’ been. Don’t know. What I’m sayin’, young man, is that I didn’t steal that sentence from no Will Rogers.

REPORTER:

No … Steal? No, no, I didn’t mean to infer that—

FANNY:

See … my Daddy always brought me up to read the newspaper, front to back, every day. So, the day our stage got into town, the first place I went to was the Sentinel—an’ I was loadin’ up with all the back issues—while Juniper was introducing herself to Sheriff Clayton Peckham.

(Looking up, smiling at a thought)

But that last part, about bein’ an alibi for his ignorance … Dang! That was good! I wish I’d thought of that.

REPORTER:

(Chewing on his pencil and looking

intently at FANNY)

Miss Barnwarmer, I’d like to get a kind of timeline for what happened. So, the first thing you and Miss Juniper did was go into the tavern?

FANNY:

(Showing impatience)

Nope. An’ if’n you check your notes … first thing I did was go to the Sentinel. On account of I wanna know about Brady City and the people and what they care about every day.

REPORTER:

(Frowning, but recovering with a

puzzled smile)

Sorry, Miss Barnwarmer. I—I just need this to go well. And there are a few things I don’t … that are just—just a little hazy. Like, well, like Miss Juniper.

(Beat)

So … Miss Juniper goes straight to Sheriff—

(He turns back a page on his notes)

—Sheriff Peckham? While you’re loading up on past issues of the Sentinel?

FANNY:

That’s right. She was lookin’ to see if there was a Thurston Flourney in Brady City.

REPORTER:

Yeeeeees. Yeeeeees. I see. So—so, Miss Barnwarmer … was—was … um … was this Thurston Flourney … was he Miss Juniper’s—beau?

FANNY:

Her what? HAW! No! Now, what’d make you think o’ that, young man? Her beau!

REPORTER:

Well … I don’t know. To come all the way to Brady City from across the United States—I just wondered—

FANNY:

No, ha-ha! no—we come to Brady City ’cause she aimed to kill Thurston Flourney—kill him dead.

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Bird’s-eye view of Scene 1: Brady City, Texas 1929 and Fanny Barnwarmer is being interviewed by a New York City reporter about her lofty career as a comedian. But the subject soon finds its true focus on Fanny’s companion, Juniper Albright, who had come to Brady City to kill Thurston Flourney.

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Juniper Albright: Seventy-six-year-old woman who was Fanny’s former companion from their first years at Brady City.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times; now in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

Voice (OFFSTAGE LEFT): Female, age indeterminate.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair CENTER, and front steps behind, descending to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT are street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1929 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., that continue as a kind of white-noise background throughout the scene. UPSTAGE LEFT, is like a separate SET placed at an angle to the main stage with indistinct, smoky walls (conveying a sense of unreality). A very plain cot faces DOWNSTAGE. This section is always in shadow when downstage is in full light—and vice-versa.

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, Aug. 8, 1929

AT RISE: FANNY sits in rocking chair facing REPORTER. She is wearing a flowered housedress and he is wearing a suit with the tie loosened at the neck and askew, a hat on the floor beside him. JUNIPER sits on the cot, in shadow. OFFSTAGE LEFT is the occasional, but faint, sound of 1929 street traffic, which is the unsonorous blend of vehicles with backfire, the whinnying response of horses, and creaking of wagon wheels.

REPORTER:

(A full anticipatory grin as of one waiting for a joke’s punchline, which then transforms to a look of perplexity when he realizes that punchline is not forthcoming)

Miss Barnwarmer! You must realize this stretches credibility to the breaking point. One just doesn’t go to the Sherriff when one wants to know the whereabouts of the person one wants to kill.

FANNY:

One-one-one! By this one yer a-one-in’, are ya meanin’ Juniper?

REPORTER:

Well …

FANNY:

No, Juniper ain’t stupid, if that’s what you mean.

[A female voice from OFFSTAGE LEFT (the street) intrudes]

VOICE:

Whatcha got there, Miss Fanny, a gentleman caller?

FANNY:

That you, Grizzy? Cain’t rightly see ya fer the dust yer automobile's kickin’ up. Now Grizzy, you jes mind yer way with yer own Howard, ya hear? an’ stay ’way from this young man who be jes' fool enough to give up his hog-sloppin’ time to court me fer a spell.

VOICE:

Haw! See ya tonight, Miss Fanny.

FANNY:

(To REPORTER)

Where was we?

REPORTER:

(Grinning)

Hog sloppin’?

FANNY:

There’s worse callin’s a body can have. So … where was I? Oh, yes, you was thinkin’ our Miss Juniper was a mite dim-witted.

REPORTER:

(Chuckling, wagging a finger, comically, at her)

No … I—

FANNY:

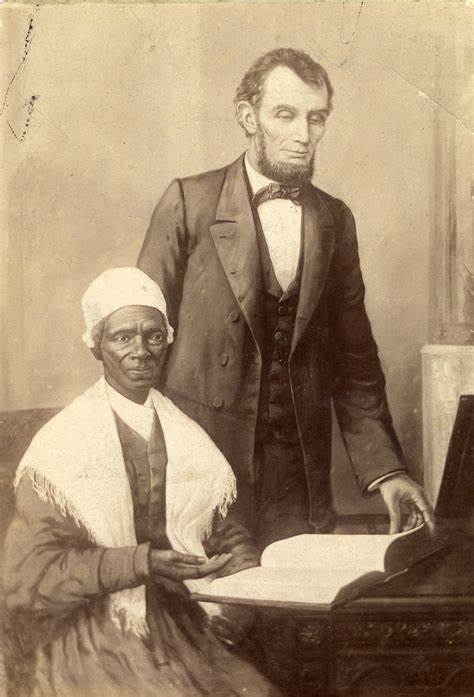

Fact is, she come from mighty fine stock. Juniper Eileen Albright—that’s her full name—was the gran'chil' of Isabella Baumfree ….

(Watching till recognition forces his jaw to drop before he goes on)

You may know Isabella Baumfree as—

REPORTER:

Oh yes! Sojourner Truth … yes, Miss Barnwarmer, I wrote an article about Sojourner Truth for the Times. She was a champion for women’s rights and abolition.

(Beat)

She was—also—was also a-a-a Negro, Miss Barnwarmer. That means Miss Juniper Albright was—she was—

FANNY:

—as white as you or me. Her hair’s a right bit curlier than mine an’ her lips a little fuller, but she's white to the point o' her skin blisterin’ in the sun. An’ beautiful. She was tall, like her Grandma, an' so—so pretty to look at.

[Full light on JUNIPER, while FANNY and REPORTER go into shadow. NOTE: hereinafter stage directions will be shortened to “Switch to”]

JUNIPER:

(Reading, stopping occasionally to dry a tear)

Oh, Jun, darlin’, I tried to keep my feelin’s outta my describing you. But I think my eyes mighta filled a mite, as I talked about you, and I watched him kinda look away to give my feelings some privacy. And right then, Juniper, I could see the story he came halfway cross country to write wasn’t gonna get writ the way his editor wanted. You know why? I could see the workings of his brain right then and there. This was gonna be your story, Jun, and my heart was about to crack outta my chest and fly away with happiness. So, after a spell, I reach out and touch his knee.

[Switch to FANNY and REPORTER]

FANNY:

(Removing her fingertips she had briefly put on the REPORTER’S knee)

So … let me jes’ tell you the story ’bout Juniper Eileen Albright.

REPORTER:

I would like that, yes.

FANNY:

Juniper’s Mama, a fine woman, near six-foot-tall, like her Mama, Sojourner, was smitten by a proper Englishman, as handsome an’ polite an’—an’ as wealthy a man as Chicago’d ever seen. He owned stock—not cattle stock, mind ya, but paper stock, like steel an’ railroad an’ such. An’ he loved Elizabeth so much. He wooed her an’ courted her … but all in them secret places, ’cause, well, she was a nigra. Juniper tells me her Mama and Daddy never got married, but not for want o’ tryin’.

REPORTER:

Of course. A white man and a negro. As it was, people probably figured she was his chattel. His slave.

FANNY:

Yep. Then, came the children. Juniper was the youngest, an’ the lightest skin of the bunch. The others—they all died from smallpox. Only Juniper lived through it. They had themselves a right pretty home outside o’ Chicago. A quiet life in the country. Well, sir, Juniper was just five when Lincoln was elected an' in a month the South started secedin’ from the Union, one after t’other. An’ she tells me—I mean, later on, she tells me, cause she heard it from her Mama—that it waren’t safe for anyone to step outside their front door ….

REPORTER:

Yes, I read that political division was rife in the north. Especially when Mr. Lincoln started gearing for war.

FANNY:

That musta been true, ’cause long about that time, one early evenin’, Mr. Albright, Juniper’s Daddy, hears a knockin’ at the door. He looks through the window to see his neighbor on the porch. But when he opens the door he finds hisself face-to-face with a gunnysack-hooded gang, and his neighbor just a-walkin’ away. By then, Juniper’s Mama was pleadin’ with the gang while they drag Mr. Albright off the porch steps an’ to the big tree in the front yard.

[From now until the end of the scene …in shadowy silhouette, JUNIPER can be seen slumped forward from the edge of her cot, her head in her hands, her body rocking]

REPORTER:

(Looking physically ill, he retches and makes a horrible face)

Oh Lord, don’t tell me they—

FANNY:

I’m tellin’ ya, son. But that’s not the worst of it. While the gang’s leader an’ two others, throw a rope over a limb, another two was forcin’ Juniper’s Mama … then Juniper herself out onto the porch. Well, Juniper’s Mama faints outright, an’ that jest leaves Juniper.

REPORTER:

Sweet Jesus, not the child!

FANNY:

—Out on the porch, with them forcin’ her to watch. By now they have Mr. Albright, a noose 'round his neck, atop an’ ol’ gray plowhorse, an’ strugglin’ to get off, but them holdin’ him on … an’ then they swats that horse’s rump, an’ Mr. Albright—

[FANNY stops in mid-sentence when the REPORTER shoots to his feet, his eyes glazed, his lips moving as he half-stumbles across the face of the porch to the parapet (stage right), then returns to slump into his chair]

FANNY (Continues):

You want I should stop fer a spell?

REPORTER:

(Tearfully, holding his tablet in one hand)

No … it needs to be recorded.

FANNY:

So, one of ’em gives that horse’s rump a swat. an’ Juniper—her head clamped atween two strong hands—is forced to watch her daddy, his eyes big as silver dollars, grabbin’ for that dang rope till his arms give out and he just swings there, twitchin’ an’ starin’.

| Author Notes |

A special thanks for RGStar for his very thoughtful review in which he enlightened me about the unimportance to the reader of the note I FORMERLY HAD placed at the beginning, to wit: "[NOTE TO READER: Remember this play is from the actors' perspective, not the audience's. What is "left" to the actor would be "right" for the audience. What is "far back" on the stage to the audience is designated "upstage" to the actor.]"

Not only is it unimportant, but as he explained (very gently, I might add), every time he came across my "Stage Left" or "Upstage Right" he found himself abstracting from the action taking place 'on the stage of his mind' and making those crazy reversals in his mind. As I told RGStar, I've removed the offender as a director would an obtuse actor who kept muffing his lines. Thank you, RGStar. Truly. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

BIRDSEYE VIEW OF PREVIOUS SCENE: The focus of the reporter’s assignment shifts from a human interest story about the famous comedian, Miss Fanny Barnwarmer, to the unfolding tragic story of her life-partner, Juniper Albright.

CHARACTERS:

| Author Notes |

NOTE TO READER: Remember this play is from the actors' perspective, not the audience's. What is "left" to the actor would be "right" for the audience. What is "far back" on the stage to the audience is designated "upstage" to the actor.

Thanks to Google Images for the picture of an elderly lady in a rockingchair. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

BIRDSEYE VIEW OF PREVIOUS SCENE: The reporter persistently brings Fanny’s focus back to the old gray horse she had earlier described Juniper’s Daddy as straddling just before the gang lynched him. When she finally admits this horse is hers, the whole backstory begins unraveling and we learn that Fanny’s father is implicated.

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Juniper Albright: Seventy-six-year-old woman who was Fanny’s former companion from their first years at Brady City.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times, on assignment in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

Messenger: Telegram delivery boy, early teens.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair, CENTER, and front steps behind, descending to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT are street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1928 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., all of which continue as a kind stew of white-noise background throughout the scene. UPSTAGE LEFT, is like a separate SET placed at an angle to the main stage with indistinct, smoky walls (conveying a sense of unreality). A very plain cot faces DOWNSTAGE. This section is always in shadow when downstage is in full light—and vice-versa

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, MId-afternoon, August 10, 1929

AT RISE: FANNY sits in a rocking chair facing the REPORTER. Stepping out of the shadowed area, JUNIPER, in a long white gown, a misty nimbus of light surrounding her, glides from the shadows toward FANNY and stops behind the rocking chair. FANNY brings her shawl together at her neck and crosses her arms.

REPORTER:

You have a chill? Should we finish inside, Miss Fanny?

FANNY:

We’ll stay here a spell, Robert. These mid-Texas summers. Poor Richard* says they’s a norther comin’ ‘Spect the Almanac's* right. It’s like y’all’s sittin’ in a tub o’ muggy, till all at once’t a chill slaps ya like a washrag ‘crost yer face.

REPORTER:

(Smiling, regarding her for a long while without speaking; then …)

Miss Fanny …

FANNY:

I know. I know. Y’all ain’t forgot … an’ I ain’t forgot neither. ’Twas jes like ya thought. ’Twas my daddy what knocked on the Albright’s door.

[At this point, JUNIPER begins to gently massage FANNY’S shoulders, bends, and lays the side of her face atop FANNY’S head]

REPORTER:

That had to be a hard truth for you to swallow. He was—was he part of that gang, then?

FANNY:

(Quickly)

No!

REPORTER:

Oh … but then …

(looking away from FANNY then back)

I don’t want to ask you, but …

FANNY:

But ya gotta …

REPORTER:

Yes, I suppose I do. Miss Fanny … were you ever planning to tell me about your daddy if I hadn’t asked?

FANNY:

I don’t rightly know. T’would a been the same endin’ if’n ya didn’t know.

REPORTER:

With all due respect, Miss Fanny, you know that’s—well, it’s just not true. I’d have wanted to know why Mr. Albright would have opened the door if he’d peeked out of his window and saw the gang standing there instead of your daddy. That goes against common sense.

(Beat)

But I think you planned to tell me anyway, Miss Fanny. It’s who you are.

FANNY:

I did. But not ’till you knowed my daddy was a good man. He was a carin’ man.

REPORTER:

I know he was all that, Miss Fanny. But he was also a carrying man, wasn’t he? He was carrying a big burden. I mean, he did owe a sizeable amount of money to Mr. Albright.

FANNY:

Robert!

[At the REPORTER’S words and FANNY’S response, JUNIPER comes around to face FANNY, and kneeling at her feet, she rests her cheek in FANNY’S lap]

REPORTER:

I’m sorry, Miss Fanny. Please forgive me. That was uncalled for.

FANNY:

No, Robert, it's me .... I left too much unsaid. Y’all don’t need no forgivin’.

(Shaking her head, vigorously)

Daddy warn’t no part o’ the gang, though.

REPORTER:

Well … and I believe that. But it still leaves unanswered questions.

FANNY:

And I was fixin’ to answer ’em… ’afore y’all asked me ’bout Daddy bein’ that neighbor.

REPORTER:

But still ... I needn’t have pounced. I’m sorry, Miss Fanny.

FANNY:

Them was rough times, Robert. E’vn ’afore Mr. Lincoln got hisself elected, back in—eighteen ’n sixty? I know I’s only fourteen then, but I remember many’s the night Daddy’n Mama be talkin’ at the dinner table ’bout the deep rumblin’ ’mong the farmers ’n ranchers ’n their nigras. They’s most called freed, but they’s moneyed chattel jes the same—an’ they sure warn’t freed.

REPORTER:

So … your folks were worried?

FANNY:

Daddy was plenty scared. An’ he warn’t alone. They’s talk ’o some states in the south secedin’ the Union, an’ Daddy tellin’ Mama the nigras … they knew. They could feel it in their bellies—an’ Daddy … he’d say you could see it in they’s eyes.

REPORTER:

The negros' eyes …?

FANNY:

Course!

REPORTER:

Your daddy had these free negros on his farm?

FANNY:

No! An’ he say that be our savin’ grace—leastways fer a while. Says you could see it in they’s eyes. They’s brewin’ fer an uprisin’.

REPORTER:

But miss Fanny, I don’t understand. Be patient with me, but I don’t—where was your daddy seeing all those—those negro's eyes?

FANNY:

I’s fixin’ to tell y’all. Daddy were one of the deacons at the Methodist church where most all the farmers therebouts ’tended. He heard ’bout the farmers’ fears from they’s own mouths. Afore long, they’s fears became his, an’ Daddy started lookin’ in the eyes o’ the few nigra freedmen ’n women what ’tended the services, an’ he swan he saw somethin’ in them eyes, too. ’Spect that’s the way fears go. Afore long Daddy organized meetins ’mong the farmers. Onest a week they was.

REPORTER:

Ohhhh, I think I see where this is going.

FANNY:

Don’t reckon ya do, young man. Jes listen. See, Daddy’s hankerin’ to bring some Christian principles o’ spirit’al love ’n carin’ twixt the farmers an’ their nigra he’p—him bein’ a deacon an’ all.

(Beat)

Well … maybe he jes gettin’ kinda preachy ’n all—don’ rightly know, but someone or ’nother o’ them farmers … they splits off—is what Daddy thinks—an’ they gits with the Army o’ Uriel.

REPORTER:

Excuse me—Say again … Army of what?

FANNY:

(Impatiently)

Uriel. Uriel.

REPORTER:

(Writing)

U-R-I?

FANNY:

E-L—A-L—I don’ know, young man. They’s the gang, though. It’s in the papers. How they’s lots o’ little Armies an’ they makes one big Army. An’ they all wear gunnysacks with a big red U on the backs of ’em. They’s mostly in the south.

REPORTER:

Like the Ku Klux Klan?

FANNY:

They’s before the Klan.

REPORTER:

(Scratching his head)

So … Miss Fanny …. The Army of Uriel got to your Daddy?

FANNY:

(Pointing to his tablet)

’Spect y’all have to … write all this ….

[The REPORTER lowers his eyes briefly and in that same moment, JUNIPER raises her head from FANNY’S lap and gazes up into her eyes]

REPORTER:

I think you know, Miss Fanny. The story needs it.

FANNY:

Ain’t never tol’ nobody ’bout it ’afore—least of all Juniper.

REPORTER:

All those years that you and Juniper were—together … that must’ve been ….

FANNY:

Figgered her mama musta tol’ her. Why stir up the coals?

REPORTER:

But … how would Miss Elizabeth have known if—

[The REPORTER is interrupted by a voice from the street behind him]

VOICE (Messenger):

(Post-adolescent, reedy)

’Scuse me, Miss Fanny—Barnwarmer … I’s Timmy—I’s Brady’s telegraph messenger.

FANNY:

(Cautiously)

Yes … Timmy.

MESSENGER:

I’ve’s a telegram from the—the Texas State Corrections Institute. Want I should read it to you, Miss Barnwarmer?

FANNY:

No!

(Placing her hand on her chest)

Bring it—bring it to me.

MESSENGER:

Yes’m.

[The MESSENGER Ascends steps, hands FANNY the telegram with multiple bows. The REPORTER removes a coin from his pocket and hands it to the boy, who, smiling, descends. FANNY presses the sealed telegram to her chest, her eyes closed tightly. Meanwhile, JUNIPER rises and slowly makes her way back to her shadowed cubicle, and sitting on her cot, remains in silhouette]

REPORTER:

Should I excuse myself for a moment?

FANNY:

No … I ain’t holdin’ back nothin’ now. You be wantin’ the whole story. ’Spect this be a part of it.

(Putting the telegram in her lap)

But ’afore I read it, I needs to put to rest the other matter—’bout my Daddy … an’ why he’d a did what he did—whether the Army ’o Uriel got to him.

(Draws in a deep breath, fingering the corners of the telegram)

Plain truth is—Daddy never tol’ Mama’n me.

REPORTER:

(Waiting a long moment for FANNY to continue before he breaks the silence)

Then … then I’m back to being confused, Miss Fanny. Didn’t you say you figured Elizabeth told her daughter—told Juniper—why your daddy did what he did? How did Elizabeth know?

FANNY:

’Cause—’Cause ’lizabeth found out about it the same’s I found out about it. It all come out in the trial.

REPORTER:

The trial!

FANNY:

But ’afore I tell ya ’bout the trial, I best be puttin’ to rest another chapter of the story.

(holds up the telegram, briefly closing her eyes before removing the sheet from the envelope. Opening it, she reads it aloud, slowly)

Miss Fanny Barnwarmer:

As warden of the Texas State Corrections Institute, it is my unfortunate duty to inform you of the passing of Juniper Eileen Albright on August 10th, in the year of our Lord, 1929.

Miss Albright died of natural causes during the overnight.

FANNY

(Stops reading, and with a large in-rush of breath, holds her free hand over her heart while still staring at the telegram):

That be las’ night! Or early mornin’—I ’member wakin’ up an’ rollin’ to my side an’ puttin’ out my arm to pull her to me, ’cause I swan I feels her shiver clean through the springs ’n mattress an’ I aims to pull her over to me an’ keep her warm.

(Shaking her head and looking away from the telegram)

But my Juniper’s been ’carcerated fer nigh on to forty years.

(Looking directly at the REPORTER)

Now, ain’t that peculiar? Don’ that jes beat all?

REPORTER:

(Smiles at her weakly, then breaks eye contact)

I’ve heard of such things. But not often.

FANNY:

Forty years!

(Sighing, she returns to reading aloud the telegram)

Miss Albright was loved and respected by all her fellow inmates, and she spoke adoringly of you. Her passing will leave a void here at the institute, and I am sure, in your heart.

Please contact my office within 48 hours to make arrangements for the shipping of Juniper Eileen Albright’s remains.

Sincerely,

Harold G. Stannel

Warden

REPORTER:

May she rest in peace.

FANNY:

(Running the back of her hand across each eye, sniffing)

Reckon as she rested in peace the minute Thurston Flourney laid in the dirt at her feet. As fer the remainin’, took her forty years o’ jes bidin’ her time fer that final rest.

(Folding the telegram and returning it to the envelope)

Now, young man, y’all want the short version of the trial? Or the long one?

REPORTER:

(Removing his pocket watch, glancing at it, then returning it)

Shouldn’t you relax before tonight’s show? I’m so looking forward to it.

FANNY:

’Spect that would be best.

REPORTER:

Tomorrow, then? After church?

FANNY:

(Chuckling)

’leven be fine, young man.

END OF SCENE FOUR

| Author Notes |

Thanks to Google Images for the picture of an elderly lady in a rockingchair.

*Referencing "The Poor Richard's Almanac", an American publication used (and still in use by some today, I believe) to predict the weather as well as offering other homespun wisdom. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Birdseye View of Previous Scene: Fanny admits her father had been the one who knocked on Mr. Albright’s door on the night the latter was lynched by a gang called The Army of Uriel (early version of KKK). She insists he was not in the gang. Fanny’s father, before his involvement, had organized weekly meetings with the farmers on how to deal humanely with their black farmworkers, who were caught up in the abolitionist pre-civil war frenzy. Before she has a chance to explain her father’s involvement with the “gang”, a delivery boy for the local telegraph company gives her the message that Juniper has died in Prison.

| Author Notes | Thanks to Google Images for the picture of an elderly lady in a rocking chair. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.Birdseye View of Previous Scene: Fanny explains to the reporter how she was in the Tavern and just beginning her act while, outside, she knew that Juniper’s plan to kill Thurston Flourney was already unfolding and she, Fanny, was just waiting to hear the shots. The Reporter was dumbfounded because her foreknowledge made Fanny an accessory to murder.

| Author Notes |

I am sorry for the rather anti-climactic Intermission that I tossed in, but you know you want some popcorn and some sweet tea. Oh, and be sure to ask if they have any stickyberry crullers. It's worth a shot. Or a pip, as it were.

Thanks to Google Images for the picture of an elderly lady in a rocking chair. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

| Author Notes |

Thanks to Google Images for the picture of an elderly lady in a rocking chair.

|

![]()

By Jay Squires

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Bird’s Eye View of Previous Scene: We see in our reporter the still respectful and courteous man, but one who is more aggressive in ferreting out the truth in Fanny’s painful past.

| Author Notes | *For those history buffs, the Great Depression began two months later, in October 1929, and many depression historians thought it was brought about largely by Mitchell's reckless banking practices. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Bird’s Eye View of the Previous Scene: The Reporter pursues Fanny’s account of her Daddy’s motives for aiding the Army of Uriel.

| Author Notes |

AN APOLOGY TO THE READER: This and the next scene are probably the most important scenes of the entire play. It would be best if it were read all of a piece. The reality is, though, that it would be so long that only the masochists among you would read it. Therefore, I must have one (and possibly two) intermissions before the final curtain.

On the other hand, to offer them in three separate posts requires me to accumulate enough member bucks to adequately promote each one. Plays have a hard time attracting an "audience" as they are. NOT to have each placed high on page one would be tantamount to a death warrant. Since I take my reviewing (to earn those bucks) seriously, and spend a lot of time on them, I won't be able to post my play weekly. Those are just realities I must live with. I hope you live with them patiently and kindheartedly, as well. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Bird’s-Eye View of the Previous Scene: The prosecuting attorney has his witness, Mr. Barnwarmer, point to each of the defendants as members of the Army.

M. Barnwarmer's testimony explains how his motive for luring Mr. Albright to the door, and the latter's ultimate death, was his fear of the Army’s reprisal against his family.

![]()

By Jay Squires

Final Words From the Previous Chapter: (Reporter) Miss Fanny … I find I won’t be able to write this story at all. No amount of good reporting will get us over this final hurdle. No one—by that, I mean no reader—is going to believe the trial from the memory of a fourteen-year-old girl.

| Author Notes | NOTE TO READER: Again, it is not easy to cut the fabric of one entire Court proceeding into a number of frayed pieces while struggling to maintain a sense of the whole damn quilt. I've lost a few of you, I know. Buh-bye. Peace. Those who've stayed seem to be still in good humor. So ... Love you all. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

The previous chapter, in a nutshell: After the judge renders his verdict of not guilty for the members of the Army of Uriel, but before he adjourns, he delivers a cruel pronouncement against Caleb Barnwarmer that leaves him emotionally broken.

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times, on assignment in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair, CENTER, and front steps behind, which descend to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT are street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1928 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., that continue as a kind stew of white-noise background throughout the scene.

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, 2 PM, Sunday, August 11, 1929

REPORTER:

That’s uncanny—it was unconscionable! The judge did nothing less than to sentence your father, right there, for murder. He swept the rest of the trial under the rug like it was dust, while engraving on the mind of the town only the memory of the guilty sentence he imposed on your daddy.

(Shaking his head, frowning)

If it weren't for Mister Jenkins …

FANNY:

Aye, Mister Jenkins, he did keep liftin’ the corner o’ thet rug, dint he, an’ pullin’ out th’ dirt. But not jes Mister Jenkins—theys other reporters what wrote theys stories in theys newspapers—’specially on account o’ what thet jedge done next.

(Beat)

But you’s right ’bout what thet jedge’s words done to Daddy. Best they’d o’ hung him. He already be a dead man inside. Th’ outside jes ain’t cetched up yet.

REPORTER:

(Lifting his finger from its kept-place in the album, where he was about to begin reading again)

Sounds like what you’re telling me is not entirely metaphorical, Miss Fanny.

FANNY:

What I’s sayin’ is Daddy’s friends an’ neighbors, they soured again’ him. His church frozed up. ’Afore long, he’s voted outta bein’ one o’ theys deacons. An’ then he had no one but fambly.

REPORTER:

Which, for practical purposes, meant he had just you to talk with.

FANNY:

An’ that be only a spell …. T’was narry a month since thet jedge’s words cast theys curse when Daddy be found ’longside River Road—twixt home an’ th’ store what supplied us twice a month—his head creshed agin a boulder.

REPORTER:

Sweet Jesus!—Geez, I’m sorry, Miss Fanny.

FANNY:

Speck’lachun was thet a rabbit or other critter spooked the horse an’ flipped th’ wagon, an’ Daddy be throwed like a rag doll agin thet boulder—the boulder what be a marker named the five-mile boulder account o’ it bein’ five miles from it to town. T’onliest boulder ’longside River Road fer twenty miles either way from town. Y’all see what I’m sayin’?

REPORTER

But … so, you don’t think a ground squirrel could’ve spooked the horse?

FANNY:

Pshaw! What with the critters alles scamp’rin ’crost the road? Why me’n Josiah’d never made a trip with Daddy what we din’t hear n’ feel the crench an’ bump o’ one or two o’ them critters under th’ wheels. Ain’t no horse gonna be spooked by no sech critter.

REPORTER:

It does sound suspicious, then.

FANNY:

By then, t’warn’t a paper in t’ county, big or small, what didn’t have stories ’bout the trial. Some in New York, even, an’ up in Boston … an’ when word Daddy died, theys a reporter from Chicago come down to interview Mama.

REPORTER:

Not Mister Jenkins, though?

FANNY:

No, no … he be busy diggin’ up information ’bout the jedge’s leanin’s an’ his part in th’ anti-abolishunist mob riots o’ eighteen an’ thirty-four … ’afore he becomed a jedge …

REPORTER:

So, the reporter who did interview your mama—

FANNY:

(A brief laugh)

He soon seed thet Mama waren’t no good source fer a story. An’ he took no stock o’ my words. ’Asides theys bigger fields t’ plow what with the endin’ of th’ trial—

(Stopping short, and staring at the REPORTER)

I swon, Robert, ain’t ya gonna read ’bout th’ endin’ o’ the trial? Or, do ya want me t’read it for y'all?

REPORTER:

(Expelling a lungful of air)

I’ve got it here ….

(Reads)

The judge patiently gathered the eyes of all present, most of whom were still reeling over the sentence he’d just delivered to Mister Barnwarmer about spending the rest of his life in the prison of his mind. Satisfied, the judge cleared his throat and began:

“Now, I have one more matter before this court adjourns. You recall, a few moments ago, I asked the defendants to approach the bench. Mister Thurston Flourney …” (and here, protruding from the armholes of his midnight-blue robe, his Honor’s arms extended like two slender white stalks, at the end of which two soft, white palms, opened like lillies in Mister Flourney’s direction.) … “will kindly approach the bench again.”

Mister Flourney did, with shoulders held well back, and head high.

“Mister Flourney, do you have the note you prepared?”

“I do, Your Honor.” He placed a small rectangle of paper before the judge.

The judge picked up the paper, smiled, and looked directly into the eyes of Elizabeth Albright. “After many years as a judge, Missus Albright, it’s been my experience that most people who have been wrongly accused of a horrendous crime such as this, but are acquitted, harbor deep anger and hatred against their accusers for what they’d been put through.”

“The four gentlemen seated there” (indicating them with an opening palm) “on behalf of whom Mister Flourney will be speaking) do not feel such anger. Nor does Mister Flourney. Do you, Mister Flourney?”

“No, your honor, I do not. We do not.”

“They don’t feel such hatred. They feel, instead—if I may act as interpreter—compassion for a widow whose husband had been cruelly ripped from her life, and had been left alone to raise her lovely daughter in a country torn asunder by war.

“While these five gentlemen, wrongly accused, but rightly acquitted, know that Mister Albright cannot be replaced as the family breadwinner, they wish to illustrate their humanity by offering this note, representing eight hundred dollars from each of the five gentlemen, and drafted by Mister Thurston Flourney, against his personal account at the First Bank of Illinois. Missus Albright, please accept this offering of four thousand dollars to help guide you and your daughter, Juniper Albright, through the turbulent and tortuous times ahead.”

The judge then smiled (the way a father would) into the cold , black face of Elizabeth Albright, whose ebony eyes stared straight at him, until the judge cleared his throat.

“And with that… these court proceedings from Lake County, in the fine State of Illinois … are hereby adjourned.”

REPORTER:

No, no, no, no, no!

FANNY:

An’ yet, thet be the whole trial.

REPORTER:

But no! Miss Fanny! Money—you told me money was never a problem with Missus Albright. She and Miss Juniper would be taken care of in perpetuity because of her husband’s foresight. But that reporter, Jenkins—I kept waiting for him to write about how Missus Albright—oh, it would have been so good—how she looked the judge square in the eyes and ripped that draft into pieces and fluttered them in his face!

FANNY:

(With an open-mouthed belly laugh)

Lord a’mighty, Robert, no! Mister Jenkins, he had it right with what he writ. ’Bout 'lizabeth’s stare—what be the same stare my Juni ’herited—what I call the rattlesnake stare. But what Mister Jenkins dint write … ’acause he dint know … was thet 'lizabeth Albright—she had better uses for thet money.

END OF SCENE 2

![]()

By Jay Squires

The previous scene in a nutshell: After Fanny explains how the judge’s virtual death sentence on her daddy left him a pariah among his neighbors and church, and may have led to his unexplained actual death a month later, she urges the reporter to read the rest of Mr. Jenkins editorial. He does, and the reader is privy to the most stunning part of the Judge’s decision.

| Author Notes | * From the above notation: Many thanks to Liz O'neil who offered me this gem of southern dialect, one of many she picked up from a group of Appalachian youngsters she taught. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

At the end of the previous scene. The reporter speaking: “So … Missus Albright figured she couldn’t risk taking out her revenge until Miss Juniper was of age. Is that right? (Not waiting) “But—but at some point … when Miss Juniper was old enough to understand her mother’s obsession … Missus Albright decided not to carry out her revenge herself, but to groom her daughter to do it instead? Is that what happened, Miss Fanny? Is that what you’re driving at?

![]()

By Jay Squires

The end of the previous scene: The Reporter is perplexed, but won’t let go of the idée fixe, despite Fanny’s insistence to the contrary, that the very determined Mrs. Albright at some point transferred her commitment to murder Thurston Flourney to her daughter, Juniper. That all changed when Fanny explains that Elizabeth Albright died after her second stroke … but before telling her daughter about her assassination plans … to which the Reporter says, “But … But somebody had to [tell her].” …. Fanny leaves us with the words, “Yep. Somebody did.”

| Author Notes | I guess I can never stop apologizing. I thought this would be the last scene, but it appears (hell, no appearing about it) that there has to be one more scene. Don't blame me that Fanny's such an entertainer. |

![]()

By Jay Squires

End of Previous Scene: Fanny had just explained how Juni’s Aunt Pikki, on the train, en route to Sojourner Truth’s funeral, had disclosed to Juni what Elizabeth had sworn her sister to secrecy about, i.e., her intention to murder Thurston Flourney. Here are FANNY’S last words, closing the scene: “They’s two wimmin, young man. … They’s two wimmin alone … on a long, hot, bone-rattlin’ train … an’ they’s headin’ fer a fune’ral. Dyin’ ’as in th’ air.”

ACT III

Scene 5

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times, on assignment in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair, CENTER, and front steps behind, which descend to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT, street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1929 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., that continue as a kind stew of white-noise background throughout the scene.

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, 4: 05 PM, Sunday, August 11, 1929

AT RISE: As with the previous scenes, FANNY and the REPORTER sit facing each other.

REPORTER:

I gather you had to find out about …

(putting strong emphasis on the next two words)

Aunt Pikki’s disclosure from … Miss Juniper, herself?

FANNY:

(Seeming to have caught the inflection)

Reckon’ as how I din’t need to. I seed it in her face thet day they step off th’ train—thet she’s a—oh! she’s a diff’runt Juni from ’afore.

(Daubing her eyes)

T’ boot—T’other Juni, I knowed I’d ne’er git back agin.

REPORTER:

To this day, you feel the pain of it?

FANNY:

Seein’ her … thet be the beginnin’ o’ th’ pain, young man. Today jes’ be the reco’lectin’ of it.

(Bracing herself)

’Course, Ain’t Pikki—she seed th’ change too. Right off … an’ she feeled turr’ble bad ’bout bein’ th’ one what brung it on.

REPORTER:

(With the same curious inflection)

Good ol’ Aunt Pikki.

[FANNY cocks her head and stares, slack-jawed, at the REPORTER for a long moment. Then her eyes seem to unfocus in an odd manner. The REPORTER watches this with his head atilt]

REPORTER (Continues):

Are you okay, Miss Fanny?

FANNY:

(Using her frail arms to push her weight off her chair)

GAO ….

REPORTER:

(Putting album and tablet on the floor, he scrambles to his feet and stretches his arms toward FANNY)

Miss Fanny! What’re you doing?

FANNY:

(Sinking back heavily into the rocker, blinking, looking for the moment confused)

Thet …? Oh, thet be a-a stage trick fer when the crowd git sidetracked.

REPORTER:

(Still standing)

A stage trick?! No, no, Miss Fanny. I noticed—oh, fifteen minutes or so ago that you seemed pale, but then I thought it was my imagination, so I didn’t say anything. What—what can I do for you? Should I send someone for the doctor?

FANNY

I’s fine, young man. It be a trick—no more. Sit down.

REPORTER:

My story’s not more important than you are, Miss Fanny.

FANNY:

We’s almost there—now sit!

[The REPORTER reluctantly complies, replacing the album and tablet on his lap]

FANNY (Continues):

They’s one o’ Ain’t Pikki’s brothers at Sojourner Truth’s fune’ral thet my Juni meeted.

REPORTER:

That would be Peter …. It was a pity—after Sojourner Truth had won his freedom from slavery through the courts, and raised him to be a fine young man—that he took a job on a whaling ship and—and he only returned to attend his mother’s funeral.

FANNY

(Who had been staring at his mouth as he spoke, her own mouth a-gape.)

How ’d’y’all know more ’bout thet than I does?

REPORTER:

I’m ashamed of myself for not taking the time to tell you, Miss Fanny … but three days ago, at the end of my first evening with you—when I made the discovery that it was no longer going to be a story about your career as an entertainer, but would, instead, be about you and Miss Juniper ... well … I hope you understand, I had to do some … snooping.

FANNY:

Snoopin ….

REPORTER:

I had to lock down some facts. So that first evening, I telephoned my editor, Mr. Villard, and convinced him I had sniffed out a bigger story than the one I was sent to write. Miss Fanny, as colorful and important as your career was, it would end up being only a human interest story, and would soon be forgotten.

FANNY:

Don’t need no sugar-coatin’, young man.

REPORTER:

I know now you’d feel that way, but I didn’t after the first day. Still, I phoned my editor anyway and what followed was twenty-four hours of intense research. You would not believe Mr. Villard’s connections … but I won’t go into that. Just know that I discovered some things that authenticate your and Juniper Albright’s background.

FANNY:

Thet be what y’alls confessin’?

REPORTER:

(Somewhat bemused)

Yes. But the net result of part of the research is this: Miss Fanny … there was no Aunt Pikki.

FANNY:

Why … sure as I’s sittin’ here, they was!

REPORTER:

Not by Isabella Baumfree.

FANNY:

Ya’ll’s sayin’ as how I ’as straytchin’ th’ blanket?

REPORTER:

Stretching the …

FANNY:

That I’s lyin’?

REPORTER:

I’m not drawing any conclusions. I’m just saying that Isabella Baumfree—Sojourner Truth—didn’t give birth to a “Pikki”.

(Reading from his notebook)

She had five children: James, Diana, Peter, Elizabeth, and Sophia. Four of the five were sired by a slave named Tom, one of the many slaves, including Isabella, owned by one John Dumont.

FANNY:

Tell me ’bout t’chil’ what din’t have Tom as a daddy.

REPORTER:

That would be Diana. Turned out Isabella Baumfree had been raped by her master, John Dumont, probably many times. One of them produced Diana.

FANNY:

Diana. That be Pikki, then. I never knowed her given name. She’s alles Pikki to me, but I did hear-tell they’s a white man somewheres guardin’ th’ woodpile.

REPORTER:

I don’t understand … guarding the woodpile ….

FANNY:

Means Pikki ’as diff’ernt from th’ rest o’ her siblin’s. ’Bout her name—pshaw! What Mama’d name her chil’ Pikki, anyhows? Pro’ly seed Diana pickin’ at her nose or th’ like, an’ … she gived her th’ name an’ it jes’ stuck. Pikki, though, she be Diana, an’ Diana … she be Pikki.

(Beat)

Now, what ot’er blanket y’all’s paper tryin’ t’ prove I straytched?

REPORTER:

(Grinning at her folksy language, he then gets serious)

I assure you, Miss Fanny, the paper’s research wasn’t aimed at pulling the wool over anyone’s eyes or stretching blankets, as you so colorfully put it. I just needed to be sure that the story I write is based on the rock-bed of truth. You don’t know how happy I am to put Aunt Pikki back in the narrative.

(Beat)

About the rest of the research … I do want to tell you about that, believe me, I do—but before I tossed Peter’s name into your narrative about Miss Juniper meeting her uncle at the funeral, and it took us far afield, I have a strong feeling you were about to mention something important to our story. So … can we first —?

FANNY:

I heered this first from Ain’t Pikki, then theys gaps filled in by my Juni. See … Ain’t Pikki ain’t seed her brother ’afore neither, so they’s some acquantuncin’ goin’ on twixt them, too. But Ain’t Pikki … she seed thet lotsa folks at th’ fune’ral knowed ’bout Juni’s daddy’ lynchin’ … an’ they read ’bout the trial an’ all. Juni ’as like the sun t’ theys earth—they’s all pulled t’her. An’ Peter be no diffurnt, once’t he heerd ’bout it from t’others. He be pulled t’ her too. But much as Pikki could tell, no one knowed ’bout ’Lizabeth’s murd’rin’ plans— ’cause I ast her.

(Beat)

Now, Pikki, herse’f … she’s lighter skinned then all her kinfolk—bout the color’ve a hik-rey nut … counta Massuh Dumont’s blood—But none’s lighter’n my Juni.

REPORTER:

So … are you saying she was—I don’t know—was she persecuted by her own for her skin color? I mean this was the funeral for one of the greatest champions of Negro rights and women’s rights.

FANNY:

Not so’s Ain’t Pikki could tell. Leastways, no one said it out loud. But she tells me theys a lotta headshakin’ an’ whispirin’ goin’ on.

REPORTER:

(Pausing to see if FANNY was going to continue, then seeing she wasn’t)

In all fairness, though, it could’ve been because they knew her daddy had been lynched.

(Beat)

So … where does Miss Juniper’s uncle Peter fit in?

FANNY:

Ain’t Pikki seed as how he alles kept his eyes on Juni from a ways off, at first. Later—like as a big hawk—he swooped down on her.

REPORTER:

Oh, my!

FANNY:

Don’ mean it thet-a-ways. Keep y’all’s mind outten th’ horse droppin’s. Pikki … she be alles watchin’ from the side, an’ she seed how he be diff’runt, an’ all.

(beat)

Th’ rest I heered from my Juni, herse’—how Peter ’peared set apart from his kin, pro’lly accounta all th’ world he be seein’ made him diff’runt—

REPORTER:

(Carefully)

And what did you make of your Miss Juni’s reaction to her uncle Peter? Aunt Pikki saw there was something different about him … how did Miss Juniper describe it to you?

FANNY:

She say he’s a big’un wit’ big arms an’ shoulders—prolly from his whalin’ work. He’s over six-foot, like his mama. But … but somthin’ more. In t’way he hol’s hissef up all higher’n everone—an’ his eyes—well dey jes’ throwed off sparks.

REPORTER

(Puffing out his chest and taking on the demeanor of a superior acting person)

He had a kind of swagger, then? Like he was proud?

FANNY:

Kindly like he’s better’n t’others, but without sayin’ it. An’-an’ … Juni say he make her feel better’n t’others, too. Soon … soon he be comiz’ratin’ ’bout ’Lizabeth.

REPORTER:

You mean—

FANNY:

’Bout her apop—’bout her stroke.

REPORTER:

And you’re sure he didn’t know about Elizabeth’s plans before he talked—?

FANNY:

He only knowed ’bout ’Lizabeth feelin’ too poorly to come. They all knowed thet.

REPORTER:

Aunt Pikki couldn’t have told him when they were getting acquainted as brother and sister? After all, She did seem to find it hard to keep a secret.

FANNY:

Ain’t Pikki din’t tell nobody. Least ways she say she din’t.

REPORTER:

But he knew about it, just the same, didn’t he? Oh, Miss Fanny, please … Forgive me, but something—or someone—had to light a fire in Miss Juniper’s soul … that changed her into the driven woman she was when you saw her step off that train.

(Beat)

No one knew Miss Juniper as intimately as you. Do you think that Aunt Pikki’s breach of Elizabeth’s secret on the train would have been enough to totally transform your Miss Juniper?

FANNY:

No … no, Robert … Seemed as sech Ain’t Pikki’s words be jest th’ tick what burruhed under my Juni’s skin—leavin’ jest an angwishin’ itch …

REPORTER:

(Slowly. Deliberately. Keeping his eyes fixed on FANNY’S)

Miss Fanny … Did your Juni tell her uncle Peter … that, before her stroke, Elizabeth—his sister—had planned to kill Thurston Flourney?

[THE HEAVY CURTAIN ON THE STAGE GIVES A JUDDER … BUT STAYS OPEN]

END OF SCENE 5

| Author Notes |

As this scene has drawn to a close and I look out on your faces in the audience, I am more aware than ever before that I have failed you. You may have been counting on the curtain call at the end of today's scene. Your maid has prepared your food at home and it is sure to get cold before this play's final act-and you're allowed to leave the theater. (Oh, yes, the doors are locked and chained!)

Before I began writing this scene, I had every intention of covering all the bases, tying up all the loose ends, and leaving y'all a tidy package. I'd even told some of you that in my comments that attended your last reviews. In the ordinary course of playwrighting, my intentions would have been fulfilled. I'd have accomplished those ends in the editing process. But looking at that blank screen I faced a week ago, I had to solve a couple of problems. Just being told by Aunt Pikki that her mother had planned on murdering Thurston Flourney, would NOT have been enough to bring about a complete transformation in Juni, and make her driven to kill Thurston Flourney. (And you'd have picked up on that, too.) It took something else. That "something else" was Peter, Sojourner's son. To make his presence that powerful, I had to make him a special entity. So, I got hung up on the character of Peter "Baumfree". He wouldn't let me go. So, if you're looking for a scapegoat to blame for your cold dinner, blame Peter. Not me! |

![]()

By Jay Squires

End of Previous Scene: Robert was wondering aloud to Fanny whether: “Aunt Pikki’s breach of Elizabeth’s secret on the train would have been enough to totally transform your Miss Juniper?” And it was followed by Robert’s final words of the scene: “Miss Fanny … Did your Juni tell her uncle Peter … that, before her stroke, Elizabeth—his own sister—had planned to kill Thurston Flourney?”

ACT III

Scene 6

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times, on assignment in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair, CENTER, and front steps behind, which descend to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT, street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1929 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., that continue as a kind stew of white-noise background throughout the scene.

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, 4:20 PM, Sunday, August 11, 1929

AT RISE: As with the previous scenes, FANNY and the REPORTER sit facing each other.

# # #

FANNY:

I don’ spect as so. I don’ ’spect my Juni knowed anythin’ ’bout her mama’s plans ’til she seed her uncle Peter.

(Glancing up and to the right, as though dragging down words and images to her mind)

My Juni say she seed Peter swoop down on her like he be a hawk an’ she be a-a lone nestin’ critter. He seed her standin’ alone from where he be conversatin’ with a bunch o’ theys kin a'ter the fune'ral broke up—prolly Ain’t Pikki be there with ’em—an’ he swoops down on Juni, an’ he plops down ’aside her, an’ ...

(introducing her thin shoulders into an eruption of tremors)

an' kindly-like shakes out an’ ruffle his feathers.

REPORTER:

(Smiling)

You like that image of him, don’t you, Miss Fanny? A hawk. A killer. You didn’t like the man, did you?

FANNY:

’Til the day he died, Glory be to God, I din’t. I het th’ man—Thet be th’ truth! I het th’ pwoison he dripped in her—the—the pwoison what got inside her an’ dried up all her beaut'ful inn’cence an’—an’—

[She suddenly thrusts both hands to just below her neck and clamps her eyes shut, her chest heaving]

REPORTER:

(Leaping to his feet, tablet and album sliding to the floor, and glancing over his shoulder, frantically)

Okay, that’s enough! I’m calling the doctor!

FANNY:

(Dropping her hands, pleading)

No! You turn back ’round, Robert! We’s so close—so close! I jes go through me some angwishin’—us wimmen, we do thet. Ain’t nothin’ wrong. Doc Hayhurst jes’ laugh at y’all fer worryin’! Now, sit y’sef down an’ give me back my album. I bes’ be pertectin’ it, meself.

REPORTER:

(Retrieving the album and giving it to her with a concerned look on his face, he sits, shaking his head)

I don’t want to be the one to give you a heart attack …

FANNY:

Oh, pshaw! Now y’all jes’ lissun t’me an’ what my Juni tell me.

(Her chest is still rising and falling, though, with deep, but rhythmic, breaths)

Th’ ol’ black hawk, he be standin’ by my Juni with th’ pwoison jes’ drippin’ from his—his—

REPORTER:

Beak?

FANNY:

Thet be it! See? Y’all’ll make a dec'nt writer yet.

(Beat)

So, my Juni, she be tellin’ me how ’as Peter be preachin’ to her like it be th’ Gosp’l ’bout th’ law o’ man and the law ’bout what be right—an’ all th’ time he be lookin’ all o’er her like he be hankrin’ fer the bestes’ place to sink in his beak.

REPORTER:

(Speaking jerkily, struggling with the dilemma of wanting to get the story right, but fearing to engage FANNY’S emotions)

I’m sorry, but—Miss Fanny—but-but were you thinking Peter was trying to-to—trying to be more than an Uncle to Miss Juniper?

FANNY:

No! I don’t think thet. But I do know as how if’n Peter was hank’rin fer thet kind o’—whatcha call it?—prey … thet my Juni woulda follered along like thet inn’cent nestin’ critter an’ … an’ never knowed what ’as happ’nin’ till it ’as too late. A-a charmin’ black hawk he be … a-a-a slurpin’ back his pwoison at jest th' right time so as no one be th’ wiser.

(Beat)

An’ he tells her, “They be da law of man, and den they be da law what be right. They be a whole tangle o’ laws, afore abulishun what ’llowed the white massur to own slaves, but thet cain’t be the law o’ what be right. Cain’t be! Ain’t no man should own another. Ain’t thet right, Juniper? Thet’s what he say, “Ain’t thet right, Juniper?” An’ my Juni be bobbin’ her haid, an’ lookin’ up at him like a teeny peeper, waitin’ fer him to drop thet pwoison worm in her beak.

REPORTER:

(writing frantically)

Let me just get that. “ … drop that poison worm in her beak.” Honestly, Miss Fanny, it must be your years of entertaining, but you could be a poet. Please, though, don’t lose your connection with Miss Juniper and Peter.

FANNY:

Well, sir, firstus he tells her ’bout those two kinds o’ laws an’ then … blamed if’n he din’t throw in another law. “Den they be th’ law thet ’llowed da Army o’ Uriel mob what lynched yo’ daddy—who be my sist’rin’s law-’bidin’ husband—to go skat-free. Oh, I seed the papers! Oh, yeah, I readed ’em all. An’ I readed ’bout you bein’ at da trial—you be all growed up now, but you be a chil’ then with yer rag baby ... an’ I cried fo’ you, Juniper.”

(Interrupting herself with a comment)

An’ slip-dang if he din’t sneak a pulluva nose-hair or some sech trick, ’acause gets his own tears a’flowin’ in the tellin’ … an’ he say:

Oh, yeah, I cried fo’ you … an’ I cried fo’ ’Lizabeth, too—yo mama, an’ th’ sistrin I din’t ev’n know. Oh, yeah, an’ I cain’t tell ya how proud I was thet yo’ mama was fixin’ to right thet wrong what snaitched her husban’—what snaitched yo daddy ’way.”

An’ then—an’ then th’ black hawk, he say,

“Do you be proud o’ yo mama too, Juniper?”

REPORTER:

(Cautiously, and yet with conviction)

Okay, but don’t you agree that we should take your belief that Aunt Pikki wouldn’t have told Peter about Elizabeth’s plot off the table right now, Miss Fanny? It’s obvious she did, regardless of what she told you. Can we just accept it that Aunt Pikki had her weaknesses?

FANNY:

Well … she swawn she din’t—an’ she took it to her grave.

REPORTER:

Okay … but anyway … Peter was proud that his sister would seek the only justice left to her, that of murdering her husband’s murderer. I’m sorry—I don’t want you to get upset again, but can you go on from there?

FANNY:

No … if I be frownin’ it be ’acause I be tryin’ to rec’lect what my Juni tol’ me from her conversatin’ with her uncle Peter at th’ fune’ral—which I ’member so well acounta I repeat ever word near a hun’ret times to try to git to Uncle Peter’s pow’r o’er my Juni. But then they’s the letters my Juni showed me what he sent her a’ter th’ fune’ral.

REPORTER:

The letters!?

FANNY:

Yees, th' letters ... So, it's like they's two pwoisons. Theys th' pwoisons from th’ fune’ral an’ then they's the pwoisons from th’ letters—they be like two flocks o' butterflies

(holding her hands up on either side of her head and wiggling her fingers, first of her right hand, then her left)

… a flock comin’ from here an’ a flock comin’ from there and theys both flocks be aimin’ to own th’ same flower. Pretty soon, they’s jes’ one flock an’ ya cain’t rightly tell which is which.

(Beat)

But I ’member this from my Juni’s mouth. Uncle Peter, a’ter he say how proud he be, he say, “An’ den I got angry, my purty li’l niece, I got blist’rin angry when I heered thet yer mama's plans got cut short by two strokes what leaves th’ fire in her gut, but takes ’way th’ arms an’ legs she be needin’ to carry out her plans.” An’ then he finished with, ’Don’ thet make you blist’rin angry, too, Juniper? Huh, don’ it?”

REPORTER:

You’re right though. It sure sounds like uncle Peter was trying to recruit his niece ….

FANNY:

It do. Now, the next, I knowed come from one o’ Peter’s letters, not from my Juni’s recollectin’. I knowed, ’acause I keeped it here in my album. He sended it on accounta … well, see, ever since she come home all rattlesnake-eyed an’ fired up fer doin’ this, I’d be tryin’ to talk sense into my fool Juni’s haid, thet this warn’t her fight. An’ I do b’lieve she be comin’ ’round an’ I knowed she tol’ him so in a letter, ’cause o’ his letter thet he sen’ back.

(She fishes the letter from the album and holds it out to the REPORTER)

REPORTER:

(Reading aloud but slowly, having difficulty with spelling)

My Dear Juniper.

I get ur letter. I see u startin to dout my truth-tellin. So, I best show you agin what the truth be. I wisht u is here. It be hard cuz the truth be here in my eyes. But U cant see my eyes, can U? So jus U try to pitcher in yer mind talkin direct to my face here.

Littul Juniper, U seed the truth here afore U leaved and U hold it there inside U a spell. How be it difrunt now? U say U be proud of the truth my daid mama fight fer. An U say U be redy to fight fer her truth now—even tho she be daid. Truth be truth! How be Ur mamas truth diffrunt?

Juniper, lissun to Ur oncle. Back near tweny year ago, durin the War of the Rebelyun, theys a lotta Yankee boys, yunger then U, be givin theys lifes—I mean dyin, Juniper—fer the truth. They be in the mud an freezin, an they bones be aken. An sumtimes they fergit why theys evun here. Sumtimes. So, they rekalect fer each othur. Kindly like I be rekalectin fer U now. An like as how the soljurs, they be rekalectin theys fightin an theys dyin fer the truth thet slavery is evul—U need be rekalectin thet Ur daddy be linched by Thurston Flourney, an Thurston Flourney be evul. An evul need be done way with. Evul need be kilt. That be Ur mamas truth, Juniper. An U be dammed—U be dammed an U be burnt in Hell if it aint gon be Ur truth too!

Oncle Peter

[In the silence that ensues after the REPORTER finishes the letter, he folds it and stares at FANNY, slowly shaking his head]

REPORTER (Continues):

To think that this letter was written by an uneducated, illiterate man, Miss Fanny. As far as rhetoric goes—as far as the manipulation of half-truths goes, he was a genius!

(Hands the letter back to FANNY)

FANNY:

(Eyes filling)

Why would he do thet? Why would he do thet to my Juni?

REPORTER:

Aw, Miss Fanny … probably because he could!

(Reaching over and patting her hand)

Maybe for the same reason he stayed away from his mother and only returned for her funeral … because he was only truly alive when he was outside of her shadow. If I’m right, Miss Fanny, then your Miss Juniper was simply an opportunity for his genius to flourish. Without a formal education … unable to read and with just the rudiments of writing, he was, nevertheless, a brilliant and dangerous man.

(Beat)

Miss Fanny, while all the time you tried to dissuade Miss Juniper … did Elizabeth ever catch on to Juni's transformation that was happening right under her nose, as it were?

END OF SCENE 6

| Author Notes |

This is a long one .... But as Miss Fanny would say, "We's so close t' th' end. So Close!"

Hell, she doesn't care what I think! Oh, and if you had read "To the Friends of Fanny Barnwarmer" maybe you'll agree with me now, after having read this scene: Wouldn't it have been grand if I had had the foresight to have brought Fanny along for the Funeral? Wouldn't it have been better than having Fanny explain how she remembered Juni's and Uncle Peter's words so clearly because she had repeated them a hundred times. Clearly, Ben Franklin was right. "An ounce of prevention IS worth a pound of cure." |

![]()

By Jay Squires

Parting Dialogue from Previous Scene: (REPORTER): Miss Fanny, while all the time you tried to dissuade Miss Juniper … did Elizabeth ever catch on to the transformation that was happening right under her nose, as it were? (Repeated below)

ACT III

TO CURTAIN

CHARACTERS:

Fanny Barnwarmer: Eighty-five-year-old woman with plenty of spark and sizzle still in her. Has been performing at the Tavern for forty-four years.

Reporter: Mid-thirties. Works for the New York Times, on assignment in Brady, Texas to write a human-interest story on the famous Fanny Barnwarmer.

Herbie: Son of Brady Inn’s owner. Has been given the assignment to take the Reporter to the train station.

SETTING: Front porch of Fanny Barnwarmer’s home. Rocking chair, DOWNSTAGE RIGHT, facing kitchen chair, CENTER, and front steps behind, which descend to street level with a flowerbed to the side. OFFSTAGE LEFT, street sounds of traffic: of vintage 1929 cars, some horse whinnying, etc., that continue as a kind stew of white-noise background throughout the scene.

PLACE/TIME: Brady Texas, 4:20 PM, Sunday, August 11, 1929

AT RISE: As with the previous scenes, FANNY and the REPORTER sit facing each other.

###

REPORTER:

Miss Fanny, while all the time you tried to dissuade Miss Juniper … did Elizabeth ever catch on to the transformation that was happening right under her nose, as it were?

FANNY:

Not so’s a body could tell. Mama ’Lizabeth, she jes’ be layin’ there, those big brown eyes th’ onliest thing be movin’.

REPORTER:

But surely, behind those eyes … thinking was going on.

FANNY:

(Showing some annoyance at his questions she couldn't answer)

Mama ’Lizabeth died ’bout a week inter th’ new year. Th’ year o’ eighteen an’ eighty-four. I a’ready telled ya ’bout th’ bequeathin’.

REPORTER:

Yes, you did. So, Elizabeth died in eighteen-eighty-four. And … still—a whole year passed before you left for Texas.

FANNY:

Y’ain’t lettin’ nothin’ git past y’all, are ya, Robert?

REPORTER:

But why? I thought she had the spirit in her after that last letter. So, why did she wait a year?

FANNY:

(A weary sigh)